Dinko Fabris - The Inspiration of Astronomical Phenomena VI. Proceedings of a conference held October 18-23, 2009 in Venezia, Italy. Edited by Enrico Maria Corsini. ASP Conference Series, Vol. 441. San Francisco: Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 2011

Galilei Vincenzio juniore

Carta 146r Vincenzo Galilei died 02 july 1591 Copia dell'atto di inumazione di Vincenzo di Michelangelo Galilei

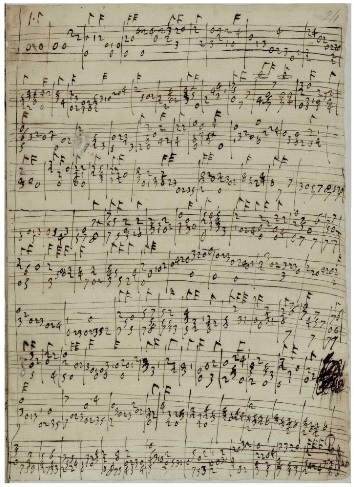

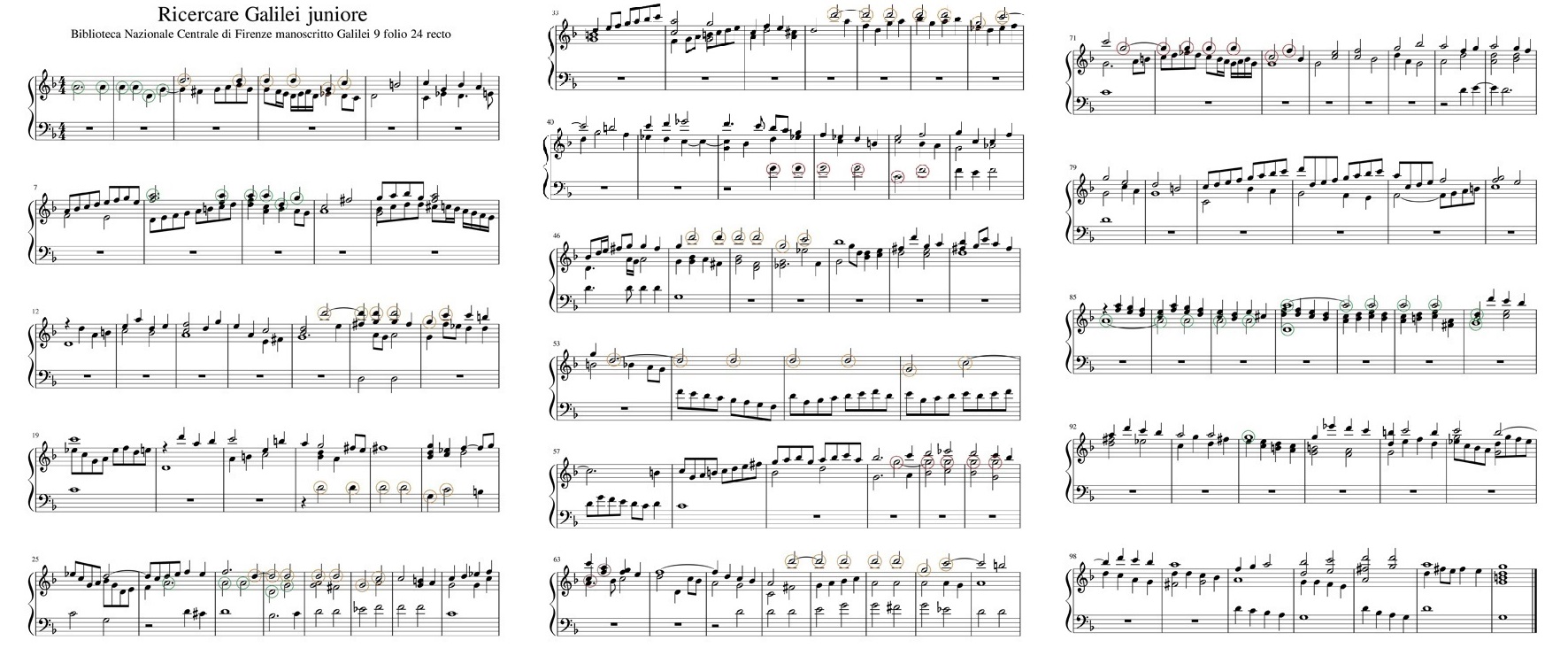

“In the miscellaneous manuscript Anteriori di Galileo 9 of the National Library in Florence, a collection of madrigals copied in “reversed score” by Vincenzo Galilei (in order to prepare lute intabulations), a single sheet can be found in a different hand, which includes a manuscript Ricercare intabulated for solo lute probably at the end of the 16th century.

This sheet is attributed to “Vincenzo Juniore” in the Library catalogue. The style of the music, written anonymously at the very end of the 16th century, is too modern for Vincenzo (death in 1595) and too old-fashioned for both Michelangelo or his son Vincenzo Jr.: even without any evidence, I like the idea that this could be the only remaining piece of lute music composed by the young Galileo Galilei.”

Based on creative association two side paths are being followed: that of a sunny metaphor by Vincenzo Galilei and the trail of a soldier into the service of Duke Maximilian of Bavaria.

During these investigations the ongoings of Michelangelo Galilei stands prominently in the spotlights, but that reveals nothing about the final conclusion.

Vincenzo father of:

Galileo father of:

Virginia

Vincenzo

Michelangelo father of:

Vincenzo

Melchilde

Cosimo

Alberto Cesare father of:

Albe Cäsar

Bibliographisches Quellen by Robert Eitner 1900 - 1904

The Quellen lists 1635 as the time for his studies.

Little Ice Age A cold

BMLO - one child Albe Cäsar based on the Bibliografische quellen

Musik in Bayern Dieter Kirsch Michelagnolo Galilei und seine Familie 2006 Band 71 - one child Franz Nestor based on Kirchenbücher der Pfarrei Unser Lieben Frau

Sie haben in München gelebt - vier Kinder source(s) not specified

Kreisarchiv serie C Fasc. 467.37

Theater und Hofmusik. No. 467.

Personalakte Albrecht Cäsar Galileis

Dieter Kirsch identifies the son as Vincenzo Galilei. Musik in Bayern 2006 note 59

The son is understood by Claude Chauvel as Alberto.

Il primo libro Minckhoff Edition Introduction par Claude Chauvel 1988 note 22

CD Michelagnolo Galilei by Anthony Bailes 2013 booklet page 10

Sr Renatto was a friend of the Galileis, who composed in the new French style, different as what he used to do in Italy, and was highly praised.

Claude Chauvel hesitates to link the identity of signor Renatto with René Mesangeau, of the most famous lutenists of the time in Paris and who supposedly lived in Germany until 1619.

The French Court wrote to Galileo:

"Discover as soon as possible some moon to which his Majesty's name may be fitly attached. You will gain renown, and likewise lasting riches for yourself and your family."

Marie de Medici played lute since her childhood in Florence and as Queen had constantly lute players in her vicinity.

An impatient and eager Marie de Medici shocked Italian gentlemen, who brought Galileo's telescope, and the French court by going on her knees to see the moon.

Intercession of Cesare Bendinelli 06 April 1603 Munich Staatsarchiv Oberbayern call no. HR facs. 81. Nr. 48

EN XIII. 1815 05 may 1627

EN XIII. 1870 05 april 1628

EN XIII. 1895 05 juli 1628

EN XVI. 3343 16 august 1636

Compiled in 1614 the music dates about 1580

Cesare Bendinelli: Some Recent Biographical Discoveries, Renato Meucci 2012 Historic Brass Society Journal vol. 24

The Trumpeters Guild in Munich was founded in 1623 and carefully regulated instruction.

Biografien aus acht Jahrhunderten page 207 Werner Ebnet / Allitera Verlag 2016

Alberto Cesare Galilei e Giacinto Cornacchioli a Galileo in Arcetri. Monaco, 1° agosto 1636.

In 1634 an outbreak of the bubonic plague killed 15,000 Munich residents

Anna Chiara (widow of Michelangelo), her three daughters and a son died in 1634 at Galileo's house. They perished shortly after arrival at Arcetri. Galileo's daughter

Dava Sobel 1999 page 362

Fronimo 1584 Vincenzo Galilei page 104: his library contained 3000 pieces composed by himself & 14.000 pieces by other composers

During the plundering of the city of Munich in the Thirty Years War all of his possessions perished in fire and flames. This could have included a chest with manuscripts, letters, and books inherited from his father Michelangelo.

Vincenzo - father of Galileo and Michelangelo, teached that every musician should have a library. Did the library of Michelangelo contain a part of the enormous collection of music manuscripts compiled by Vincenzo? This collection must have been the base of Michelangelo's musical education and Vincenzo's method - giving an eagle's view on 16th century composers.

Or did Guilia Ammannati - mother of Galileo and Michelangelo, use the paper inheritance of her husband to light up the stove in the period 1591 - 1620, at the peak of the little ice age (in familiar and climate sense)?

Gabrieli was the second organist in Venice, first organist was Claudio Merulo. Gabrieli was an outstanding teacher and composer and had many influential students.

Glen Wilson CD booklet Andrea Gabrieli Keyboard Music 2010.

Did Anton Holzner and Alberto Galilei study the compositions of Andrea Gabrieli, the former organist at the Kapelle in Munich and at the San Marco in Venice?

Gabrieli was a master in the use of augmentation - magnifying the length of his themes up to 4 times. Harpsichordist Glen Wilson writes that his ricercares are a quantum leap beyond previous efforts and that Gabrieli is the ancestor of Bach's fugues.

Gabrieli's themes have character and personality, there is unity by singularity and his ricercares are clear instrumental music: going where no choir is able to go.

Crossover between keyboard (organ, harpsichord) and lute repertoire was omnipresent. Many musicians and composers were familiar with both.

Monteverdi, who originated from Cremona, was choirmaster at the San Marco in Venice.

EN XVIII. 3994 19 aprile 1640 Alberto Cesare a Galileo

Cosmas or Cosmo

Johannes Kepler died in Regensburg.

EN XIII. 1829 14 luglio 1627

EN XIII. 1863 22 marzo 1628

EN XIII. 1867 29 marzo 1628

EN XIII. 1876 27 aprile 1628

In 1604 an employee of Galileo reported him to the Inquistion. Among the accusations was the testimony of Guilia Ammannati that she had him spied on and find out he was going to his beloved Marina instead of going to mass.

Marina Gamba died in 1612

Mechilde had a bright mind. She learned Latin among other things and was very popular with her Jesuit teachers who came from Rome. After her studies she went into a convent.

Michelangelo could no longer afford the house he lived in since his arrival in 1607 and moved to a cheaper house in 1627. Further impoverishment also resulted in acceptance off loss of status, resulting in a third option for Mechilde besides getting married or being a nun: she came home. Michelangelo took her out of the convent "for good reasons". The extreme strict regime of the convent turned out to be to much for her.

Galileo found an acceptable social facade for his wish to live with Marina Gamba, the woman he loved but could not marry according to social standards: she became his housekeeper.

In 1627 Mechilde lives quietly and lovingly with her father and her aunt Massimiliana Bendinelli (who took care of the household) in Munich. There were fives mouths to feed, probadly two lute students lived in.

Chiara (who in 1627 - 28 took care of the household of Galileo in Florence and had brought her children besides Mechilde) was married to Michelangelo. Her sister Catharina was Chief chamber servant of Maria de Medici.

Did Cesare and Elana had three daughters? Or is Catharina the same person as Massimiliana and was Michelangelo's household run by the former Chief chamber servant of the Queen of France?

He was creative: as a young boy he showed sculptural talent making a horse and carriage and other things out of wax without any tools.

He was instructed with great diligence by his father. At the age of eight he performed with great success for the duke and eight princes.

Karl Trautmann - Jahrbuch Münchener Geschichte 1889

Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv HZR 77, 78

Music, Piety, & Propaganda - Alexander J. Fisher 2014 page 222

"Bleibt noch einen Blick auf Vincenzo zu werfen, den man aus heutiger Sicht nicht so streng verurteilen würde, wie es seine damalige Umgebung tat." Michelagnolo Galilei und seine Familie Musik in Bayern 2006 Band 71 Dieter Kirsch page 23

In Rome he felt alone and abandoned by his family, behaved accordingly - and as a result was abandoned and left alone. "Why, do you believe, did my father and my uncle sent me here? Maybe because my father couldn't teach me, like someone else? They have done that, because they don't care about me."

Biographers regularly parrots Michelangelo's sons were difficult. This is a moral verdict framing Alberto, Cosimo and Vincenzo - and is grounded in Vincenzo's experience in Rome.

From the letters Michelangelo wrote to Galileo we can trace how important the musical education of his sons was for him - he never lost this interest out of his sight, no matter how high the tensions would go.

Michelangelo sought explanation of the unfortunate complications in the fact that Vincenzo's wet nurse had been a whore. From our distance in time that sounds more like a verbalisation of a rather negative coloured personal affect than as a logic explanation or analysis.

EN XVIII. 4073 Alberto Cesare Galilei in Monaco a Galileo in Firenze.

Galileo Galilei e Il mondo Polacco Karolina Targosz 2002

The royal secretary Girolamo Pinocci paid Vincenzo's travel bills to Warschau (february and march 1645) and Lublin (juli 1647).

The son of Michelangelo

In biographies both are sometimes confused with Vincenzo Galilei - the father of Galileo and Michelangelo.

Vincenzo Galilei's experiences in Rome were not that much different as the one from Vincenzo Galilei.

Galileo at Work: His Scientific Biography Stillman Drake 1978 page 449

A. Favaro, Amici e corrispondenti di Galileo Galilei , XII, V. G ., in Atti del R. Istituto veneto di scienze, lettere e arti , LXIV (1904-05) pp. 1349 -1377

PP 139 - 148 N. Vaccalluzzo, Le rime inedite di VG, in Galileo letterato e poeta, Catania Catania in 1896

PP 171 - 216 D. Ciampoli, Nuovi studi letterari e bibliografici, Rocca San Casciano 1900

Singing Dante by Elena Abramov-Van Rijk 2014

Galileo, Dante Alighieri, and how to calculate the dimensions of hell by Len Fisher 2016

Vincenzo was a member of the Accademia degli Svolgliati which discussed literature. There he met John milton who he introduced to his father.

About 3500 verses in autograph cod. 2749 dated 1647 titled "Rime diverse di Vincenzo Galilei" are kept in the Biblioteca Riccardiana di Firenze.

These poems play with the classic Renaissance models of Dante and Petrarca.

In 1580 Vincenzo - father of Galileo and Michelangelo, had presented the first experiment with the stile recitativo before the Florentine Camerata. The text chosen was an exerpt from Dante's Divine Comedy.

The literal interpretation of a piece of poetic imagery can lead to absurd results. The Florentine academy asked Galileo to calculate the exact dimensions of hell, based on Dante's description.

Galileo calculated that the roof of hell would have to be 600 kilometres thick. Galileo soon realised he errored. Scaling up the proportions of Florentine's Dome to a geographic level has consequences. Augmentation means change.

Autograph cod. It., IX, 138 (= 6749) under the name Licinio Fulgenzio Nej in the Biblioteca nazionale Marciana di Venezia is also written by Vincenzo - son of Galileo. This volume dates back to 1648 and contains eighty-four prophecies.

The poetry is witty, the verses have a concise form and are demarcated by lambent rules. It can be appreciated as l'art pour l'art avant la lettre & at the same time can be taken very serious in its implication, consideration and perception of how the world turns. A major role is given to the music of chance.

He was Hofdiener to the court in Prague during the time Kepler worked there.

Or is it wiser to say that Vincenzo was very capable of constructing his own lute and that he had the mindset of a clockmaker which explains why he enjoyed building mechanical music boxes, like Hassler or Bendinelli?

EN XIII. 1939 Maria Celeste a Galileo. The Galilo Project

D. Sobel translated chitaronne as guitar.

On the Origin of the Chitarrone by Douglas Alton Smith 1979

Hemelse boodschappen NRC 31 december 1999 H. Brandt Corstius: "Couldn't Galileo have been more brave about the fate of his daughters?"

Francesca Caccini at the Medici Court by Suzanne G. Cusick 2009

Primo Libro delle Musiche Francesca Caccini 1618 Florence

Celeste amore Maria Francesca Caccini page 17 Maria, dolce Maria: surprising harmonics and profound word painting.

Costellazione della Pleiadi Galileo Galilei

Never before seen stars leaped out of the darkness Galilo Galilei

Carolyn Raney credits Caccini with creating strong and active bass lines, particular individuality, lyric beauty and great variety.

Francesca Caccini, Musician to the Medici, and Her Primo Libro 1971

In 1609, when she was still a child in Padua, Galileo had set a telescope in the garden behind his house and turned it skyward.

In the words of Dava Sobel: "Never-before-seen stars leaped out of the darkness to enhance familiar constellations; the nebulous Milky Way resolved into a swath of densely packed stars, mountains and valleys pockmarked the storied perfection of the Moon; and a retinue of four attendant bodies travelled regularly around Jupiter like a planetary system in miniature."

In 1616 Virginia became a nun and adopted the name Maria Celeste, in a gesture that acknowledged her father's fascination with the stars.

She made little embroidered collars and cuffs for her uncle Michelangelo and his children. Little Alberto stole her hart.

Virginia might have followed private music lessons taught by Francesca Caccini, who is known to have participated in the conversazione at Galileo's home. Performances of Francesca's "little girls" (princesses, ladies-in-waiting, female court personal and various other pupils) are mentioned in reports of activities at the Medici court.

Francesca Caccinni was a virtuoso on the lute, guitar and harpsichord, poetess and gifted composer serving the Medici court. The French King said Francesca was a better singer than anyone in France. In 1614 she was the Medici court's most highly paid musician. She was a master of dramatic harmonic surprise.

Francesca's book of 1618 reveals her to have taken extraordinary care over the notation of her music. Especially the ornamentation is written-out brilliantly. She was cited by contemporaries for her training in counterpoint.

Maria Celeste taught canto firmo to the novices and had daily duties with the choir. The Convent in Arcetri was neither rigorous nor wealthy.

Her chitarronne, a gift from Galileo, had collected dust in 1629 and was replaced by two updated breviaries, for her and her sister.

Michael Engl Gallilei & Michael Angl Gallileis by his widow Maria Klara (Anna Chiara)

Michaal Agnolo & Michael Angeli Gallilai by Maximilian I

Michaëlis Angeli by Georg Victorinus

Michaeli Archangeli and Michaelis Archangeli by Johannes Donfrid

Michael Agnolo by Wolfgang Caspar Printz

Michelagnolo by Virginia; Galileo; Livia; Lorenzo Petrangeli; Il primo libro; Contrapunti a due voci

Michelagnoli by Georg Draud

Michelagniolo by his mother Giulia Ammannati

Michel Angelo by Girolamo Mercuriale

MichelAngelo Galilei fiorentin by Besard

Michelangelo Gallilei by Aurelio Gigli

Michele Angelo Galilei by Johann Gottfried Walther

M.Gallileus Italus by Georg Leopold Fuhrmann

Ten children: Michelagnolo Galilei und seine Familie 2006 Band 71 Dieter Kirsch page 12

A life with ample misery.

He lost his father at young age. His mother had a terrible temper, she was prickly and quarrelsome and never tired of pointing out that she came from a very noble family from which also came the famous cardinal Jacopo of Pavia and that they have to live accordingly in splendour (her father had the habit of beating his family when he returned from the tavern).

Michelangelo's obligations as a young man to contribute to his sisters dowries surpassed his year income manifold.

He did not improve a tool that would change the world.

Three of his ten children died young. He banded his oldest son.

The war had a devastating effect on his circumstances. War taxes caused inflation in 1623 which led to a tenfold increase in living costs and he desperately asked his brother many times for help.

The plague hunted and got him.

19th, 20th & 21th century literature (in the many biographies about his brother) did not spare him.

Some assume that the financial burden to provide for his family urged Galileo to make inventions like the proportional compass and the thermometer to earn money.

Michelangelo Galilei was a first-rate composer.

Vincenzo Galilei and the Instructive Duo by Alfred Einstein 1937

Didactic music in printed Italian collections of the renaissance and baroque by Andrea Bornstein 2001

The preface of the Contrapunti specifies da cantara e sonare. Its purpose was instructing the young how to sing, play and compose. Most pieces lean to instrumental music. According to the keys the instruments asked for are either treble viol with viola da gamba or violin with viola.

Livia Galilei a Galileo 1593

Booklett CD 1988 Paul Beier Michelagnolo Galilei page 11

POLSKI WĄTEK W ŻYCIU I SPRAWIE GALILEUSZA Polish thread in Life and Question of Galileo, "Galileo Galilei e il mondo polacco" by Bronislaw Bilinski (1969) with supplements, Karolina Targosz

Partly translated

Euridice: among the singers were Francesco Rasi and Francesca Caccini. Claudio Monteverdi was likely among the audience.

Michelangelo returned from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth to Padua in 1599 and 1606 (possibly on the run for an outbreak of the plague in Lithuania in 1605 or the threatening insurrection by the nobility against the King).

On his returns he lived at his brother's house in Padua, playing lute and composing music. Attempts were made to introduce him to the court of the Medici - without result.

In october 1600 Marie de Medici married King Henry IV of France in Florence. Part of the festivities was an opera, the earliest to survive. It was composed by Peri in the new style Vincenzo Galilei had envisioned.

Upon arrival in the Polish_Lithuanian Commonwealth Galileo expected Michelangelo immediatley to pay 200 crowns for Livia's wedding outfit, 600 crowns more in cash and 200 crowns a year for a five year period for the dowries of his sisters.

Michelangelo didn't respond for a long period to Galileo's letters. In 1608 he wrote: "I cannot pay the 1,400 crowns to get rid of the debt to our two brothers-in-law. You should have given my sisters a dowry in conformity with the size of my purse and not in conformity with your own ideas of what is right and fitting. I sent you fifty crowns and would do more if I could."

EN X. 174

This actually makes sense. Galileo had a scanty stipend in those years but in biographies is praised for his generosity to provide silken bed-hangings and black velvet dresses with light blue damask (which costs a fortune) for his sisters Virginia and Livia.

Driving force behind keeping up appearances: Guilia Ammannanti - mother of Galileo, Michelangelo, Virginia and Livia - did not have harmonic family life as her primary concern.

The Lithuanian Roots of Igor Stravinsky by William J. Morrison 2013

We have almost no facts about his years in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Here it might be noteworthy to observe that in 16th century Lithunian folkmusic a unique and significant form of three-voiced polyphony was very popular, called the sutartinės (meaning universal harmony). It took hold of the listener with its somberness.

They were sung by women, but men performed instrumental versions on wind instruments or the traditional kanklės, a plucked string instrument.

Special characteristic of this music was its bitonality.

This challenged musical axioms of Michelangelo's father (concepts about centre, dissonance and consonance), who had written that many lessons could be learned from simple songs of the populace, putting it to a test.

The poetry of the sutartinės is very visual. Michelangelo might have heard this tunes for 14 years on the streets, at gatherings and weddings.

Three centuries later Igor Stravinsky got his hands in Warsaw on an anthology with 1,785 sutartinės wedding songs and borrowed five for The Rite of Spring - widely credited for popularizing bitonality.

Stravinsky admitted borrowing number 157 Tu mano seserėle: You my sister, a song with wedding advice: do not marry above your position.

The (Rite of) Winter at the turn of the 16th century was one of the coldest in the last thousand years and Michelangelo's sister Livia desperately wanted to escape another force of nature: her mother, but was determent not to go to a convent. Her way out was a bitonal constellation: getting married, but that came with a price: a dowry had to be paid.

The marriage contract dated 01 january 1601 of his sister Livia noted that Michelagnolo lived in Litauen. A letter of Galileo dated 20 november 1601 is addressed to Michelangelo in the city of Vilnius.

Payed lutenist under Lassus:

1552 - 1568 Lienhart Reillstorffer

1561 - 1570 Hans Kolman

1570 - 1579 Giovanni Gabrieli

1573 - 1573 Cesare Cremonese

1573 - 1581 Cosimo Bottrigari

1574 - 1575 Josquin Salem

Ein ältest Orchester 1530 - 1980 Hans-Joachim Nösselt

Singing poetry in compagnia in 16th century Italy by Phillippe Canguilhem 2016

Letter Giovanni Mauro d'Arcano 16 december 1531

Bottegari *1554 - 1620

The splendour of the flourishing musical chapel and chamber music of the court of Munich was unmatched. Two styles bloomed: traditional polyphonic music and the new style of accompanied monody introduced by Lassus's sons.

The Florentine lutenist and singer Cosimo Bottegari, who sat at the table of the Bavarian court as gentiluomo della camera in the years 1573 - 81, was likely acquinted with Vincenzo Galilei.

Bottegari's lute manuscript contains a formularic Aria in terza rima composed to sing any terza rima, which in practice could have included Dante's epic poetry.

That Dante's Divine Comedy was sung is demonstrated by an example as early as 1531 when of an extract of Dante's Inferno canto III (entering the gate of Hell, abandon hope all ye who enter here) was performed in Rome at the sound of the lute played by Pietro Polo.

There is no mention of Michelangelo's involvement in the chapel. He played the theorbo - but no remarks about thorough bass accompaniment appear in his letters.

During his appointment there were several music directors: Ferdinand I di Lasso 1602 - 1609, Jacomo Perlatio 1609 - 1612, Bernardino Borlasca 1611 - 1625, Ferdinand II di Lasso 1616 - 1629.

Badua - Padua: Another cold, same scribe?

EN XI.522 1611 Michelangelo a Galileo

It comes from heaven and lookes like a star.

Kepler recognizes a problem, discusses several solutions, rejects them all, and passes the problem to be solved in the future. René Descartes would take up that challenge.

In 1611 Kepler published a pamphlet about snowflakes and nothing, offered as a New Year gift to Wacker von Wackenfels. (Nix = snowflake in Latin and nothing in German.)

Hortus Musicalis Novus by Elias Mertel Strasbourg 1615 with two anonymous versions of toccata page 38 IL Primo Libro

The second version has far wandering harmonic additions, raising questions about authorship.

In 1617 two toccata’s of Michelangelo were published in the Novus Partus by Jean-Baptiste Besard Augsburg

Like the compositions we know of, printed for the first time in 1615 in two anthologies – twenty years later?

The first piece of Michelangelo to appear in print - the Tocata page 23 Testudo - is squeezed in in a chapter with canzoni by another outstanding composer: Hans Leo Hassler. (At Rudolfs court in Prague Hassler experimented with automatic instruments.)

Michelangelo and his father Vincenzo are the only members of the Galilei family of whom we have scores which can be ascribed.

Celestial Sirens and Nightingales Alexander Fisher The Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music (JSCM) 2008 References 54 and 56

Filiae Jerusalem (using moveable do), Victorinus, Georg [Hrsg.]: Siren Coelestis 1616 & 1622

Printers in Munich

The motet was included in an anthology by Johannes Donfrid 1623

A Theory of Art by Karol Berger 1999 page 129 The debate continued for centuries. Rousseau formulated the same metaphor about colours as Galilei.

Melting the Venusberg by Heidi Epstein 2004 page 142 Archival evidence reveals a gaping hole between the church's theoretical reforms and the virgin's whoring music.

Sisters doing it for themselves by Laurie Stras 2017.Choirs of singing nuns were called Celestial Sirens. "Hearing these motets I understood why the bishops were so queasy about nuns' singing."

In 1616 Michelangelo delivered a motet for three sopranos for an anthology compiled by the director of the Munich Jesuits Georg Victorinus. It was printed by Anna Berg in Munich and financed by her husband Johannes Hertzroy from Ingolstadt.

The anthology captured new developments in the field of composing. Its title Celestial Sirens suggests heavenly seduction, which frames the music in a cosmic context. Michelangelo was sensitive to such poetic arrangement.

The three voiced motet starts with repeated notes and a descending fourth (the opening motiv of a canzona - chanson in French).

Did Michelangelo adress the Artusi - Monteverdi dispute about the new way of composing, with his choice for the Daughters of Jerusalem?

Artusi wondered how Monteverdi has preserved their chaste if he had made them become like a painted whore. With this colourful word-painting the beholder Artusi tried to express that he did not like it and that is was wrong, very attractive and exciting.

Against this background Michelangelo's motet was a clear artistic statement.

The polemic recapitulated the Zarlino - Galilei debate about the new practice. In his treatise on counterpoint Vincenzo had compared the function of consonances in music with colours in painting.

Virginia - daughter of Galileo, adopted the name Celeste and became a nun (Daughter of Jerusalem) in 1616. This decade celestial imagery celebrated its high days. Celeste might have conducted her Celestial choir singing her uncle's Filiae Jerusalem.

In 1616 Galileo was brought before the inquisition who reported that the proposition that the Sun is stationary at the centre of the universe is foolish and absurd in philosophy.

EN XII. 1422 Michelangelo a Galileo

EN XVI. 3331 La gran peste killed Michelangelo

Grab Michelangelo was buried on the Friedhof an der Frauenkirche München.

According to Michelangelo if the only advantage of the book would be to show the world that he knew something and what he was capable of, it would be worth the effort and the money spend.

The money spend is Galileo's. We have no record of Galileo's opinion on Michelangelo's view. There is a gap of letters for seven years. When resumed, you get the impression that in previous years there has been no contact.

Michelangelo Galilei and Esaias Reusner by Paul Beier 2011

Esaias Reusner Junior by Grzegorz Joachimiak 2012

Based on stylistic features François Dufault (Paris) and Esaias Reusner (Vilnius) can be counted among Michelangelo's intellectual heirs.

Michelangelo didn’t want to leave the city to supervise the printing, this would harm the musical education of Vincenzo, so the printing was taken to Munich.

Page 743 On the same page: Mylius.

The book was sold in foliants: the buyer had to bring it to a binder to make a book out of the sheets.

London K.3.m.21 and Krakow G140

Both have a doppelganger: a handwritten copy of London K.3.M.21 is CH-Bfenyves Pauer Privatsammlung Albert Fenyves Frontespizio

Krakow G140 is bound with Johann Daniel Mylius 1622 Thesaurus Gratiarum. 38 pieces of Il Primo Libro are included in the Thesaurus: an engraved doppelganger.

The Thesaurus pieces are in a different pattern of beats, showing different groupings. Augmentation changes the view.

Mylius was lutenist of the Hauptkirche in Frankfurt. He settled as Korrektor in Buchdruck, which seems unlikely, taken into account the tsunami of mistakes flushing through the Thesaurus.

Berlinka Troop movements in WOII caused Krakow G140 to be out of sight for decades.

Overview on all sources.

Passemezzo Antico U. Meyer

Although phrasing the seemingly light footed dances can be as demanding as the multi voiced toccata, there is a difference in degree of technical difficulty of Michelangelo's survived music before publication of Il Primo Libro & afterwards.

An explanation might be that the music (after) in the hand of Albrecht Werl en Aegidius Rettenwert is composed for teaching his pupils, and the music in the anthologies (before) is for showing the world what he is capable of.

Rettenwert enriched Michelangelo's surviving works with specials forms: ballet and intrada (an opening piece).

In 1870 it was stated that some say Michelangelo's book was a dissertation on the flight of swallows. The Private Life of Galileo 1870 Macmillan page 135.

This may indeed be the case: English Collins Dictionary - English Definition & Thesaurus 2000 A flight of swallows:

- a soaring mental journey above or beyond the normal everyday world

- a journey through space

The front specifies: nuouamente composto e dato in luce in Monaco di Baviera. Newly composed in Munich: based on this description we can deduce that his output as composer before his arrival in Bayern did not found its way in this book.

The preface mentions: "be careful when playing in b dur to tune the eighth course with the e in the tenor and when playing in b mol with the D of the same string, which is an octave lower."

The music is written for a lute with ten courses and ten frets on the neck.

The tablature used is French with basses noted as ciphers for the four lowest courses.

Sonate can be understood as instrumental music - in opposition to cantate: for voice.

The toccata are classic Venetian: opening slow and alternating passage-work with fugal episodes. In Venice they grew out of improvisations of the organist handing over the pitch to the choir, bridging the spoken word of the liturgy and the sung part of the service. The freedom of the toccata melodies is akin to the new recitative style, approaching speech.

The toccata are an inspiring source of motives for the dance pieces. Every piece has its own page. The tonal arrangements of the pieces practically results in the concepts of the suite.

Ten groups consist of a toccata and dance pieces: gagliarde, correnti and volte. The last two groups are variations on a bass foundation: passemessi and saltarelli.

Long arches of melody are conveyed despite the unsustained tones. Long melody lines, more suggested as sounded, are a major mark of the lute’s influence in the history of music.

The use of dissonances, embellishments and tonality is very personal.

The contrast between high and low lying passages and the craftsmanship of counterpoint are striking. Vincenzo would have been proud if he could hear this.

And as Vincenzo had catalogued a complete spectrum of affects in his 1584 Libro di liuto for accompanying poetry, so did Michelangelo demonstrate his ability to express all kind of affects in pure instrumental music.

The structure of the dances is non-strophic. The irregularity of the number of measures gives a sensation of freedom and unpredictability.

The AA BB form of the dances is a shift from the renaissance flow of melodies. Despite the repeats every passage is fresh and never the result of a template.

The suggesting of several voices with just one, called the broken style, is elaborated masterly.

There is an awareness of unity throughout the whole libro.

A sense is created that something deep and meaningful is communicated.

This music is a journey of discovery.

Michelangelo's brother was also a discoverer.

EN X. 50 Giulia Ammannati Galilei a Galileo in Padova 29 maggio 1593.

Weird-mom worries Moon Man What Galilei saw by Adam Gopnik 2013 New Yorker magazine. Guilia Ammannati *1538 † September 1620 was cold and crazy.

Would Monsu mentioned in this letter and the composer of music Michelangelo is searching for, be René Saman? Monsu being shortage for monsigneur?

July 1627 Michelangelo - on the run for the war, took his family from Munich to Florence to move in with Galileo. His family would stay there for nearly a year.

With so many skilful hands around the house a reason appears why no copy of Michelangelo's Libro Primo survived in Galileo's library: it could have been taken by a family member for use.

Little evidence exists about what manuscripts Galilei may have owned. Crystall Hall - Galileo's reading 2013 page 29

Galileo Engineer Matteo Valleriani 2010

"I like the idea that this could be the only remaining piece of lute music composed by the young Galileo Galilei".

Galileo was born in 1564. How old did the young Galileo has to be to find the equilibrium between too modern and too old-fashioned? Twenty-five and kicking? Michelangelo and Galileo differ nine years. Thirty-five and the clock still ticking?

When the clock of the convent of Galileo's daughter broke down he reassembled some parts before it was send back to the clockmaker in Munich, where Michelangelo had commissioned its manufacture.

He composed two books of madrigals, along with music for voice and lute, much of which anticipated early Baroque music. His co-invention of monody is often cited as leading to the use of recitative in opera.

Another student of Zarlino was Claudio Merulo - the first organist at San Marco in Venice. The San Marco had two organs and Merulo and Gabrieli did duel on their instruments - improvising musical dialogues.

Bardi wrote in 1634 that Vincenzo had un tenore di buona voce e intelligibile. He might have been mistaken about the tenore: the intabulated reductions in Fronimo are for a bass or baritone voice.

The title page of the Contrapunti a due voci speficies that the canto is for tenore. The composing took only a few days (two duos were composed at least sixteen years earlier, since they were included in the first edition of the Fronimo).

Translated by Robert H. Herman 1973

Part II by Robert H. Herman 1973

Music was to be viewed above all as a branch of rhetoric. His ideal was the union of music and words through monody and poetry.

The Dialogo contains three ancient music scores composed by Mesomedes, court musician of the 2th century Emperor Hadrian. It was extremely fascinating and Vincenzo tried to decode it. One song was a Hymne to the Sun.

He proposed the airs for singing poetry at the beginning of the 16th century as a model for modern vocal music in simple three- and four-part arrangements.

Vincenzo's advice for composers was to study how actors used their voices in order to express various affects: singing should imitate emotional speech. His sons were witnesses of his developments in this area.

Vincenzo Galilei's manuscript Libro d'intavolatura di liuto 1584: an introductory study by Luis Gasser 1991

Digital booklet pdf Vincenzo Galilei The Well-tempered Lute by Žak Ozmo 2014

Some people expierence lack of depth and beauty hearing this simple music & wonder if it can be heard in a row without being bored. When one judges its merits one must take into account that this music is about serving poetry and is incomplete without it. Its goal was supporting an improvised recital of text, executed with a slight prolongation of the notes so that is was close to ordinary speech. This music is declarant for a declamating performer - it blossoms besides a storyteller.

"Seguitando il mio canto con quel suono": Dante in musica nel madrigale by Marco Materassi 2017

Bardi: "Undoubtedly, this was generally liked, although jealous persons were not lacking, who, green with envy, at first even laughed at him".

The experiment of Galilei raised some perplexity for "a certain rudeness and too much antiquity that was felt".

In the decades that followed opera arose from the enormous possibilities that were created with it. From the space given to singers a new phenomenon emerged: virtuosic stars like Francesca Caccini and Francesco Rasi begin to sparkle. Soon there were stars everywhere who were able to let you experience all affects.

Johann Mattheson crisply clarified and catalogued a century and a half later again the musical wherewithal of the Affektenlehre: the doctrine of how to spiritually move the mind with music that expressed a single emotion. It became obsolete at the end of the Baroque because composers wanted to use with whatever means fantasy and intuition may suggest to express subjective feelings.

unpublished and twice rewritten.

Cosi nel mio cantar Discorso intorno 147v Vincenzo Galilei 1589 performing Dante (parlar is replaced by cantar). Typical are the many repeated notes and cadences at the end of a sentence.

Vincenzo Galilei's Counterpoint Treatise: A Code for the Seconda pratica by Claude V. Palisca 1994 "The counterpoint treatise is Galilei's most significant achievement. For prophetic vision, originality and integrity it has few equals."

It is noting dissonance examples written in two, three, four and five parts from Josquin to the present in 1591 and even adding several irregular resolutions. It presented ground rules for good practice in the modern style.

His counterpoint treatises are the first treatises on harmony in the usual modern sense. As teacher, composer and theorist he was up to date, summing up the experience of his contemporaries.

Music theory was usually of not much use to contemporary composers because it described archaic rules of preceding generations. Vincenzo's work was an exception and being old fashioned would not be a fitting epitaph.

His theories for vocal music must be seperated from his ideals for instrumental music. The complex, well-ordered art of counterpoint was admirably suited to purely instrumental music, to which it should be confined. Vincenzo liked contemporary artful instrumental music, which reached a state of supreme excellence. Claudio Monteverdi would likewise embrace two ways of composing.

9 or 10 musicians 18 or 20 hands

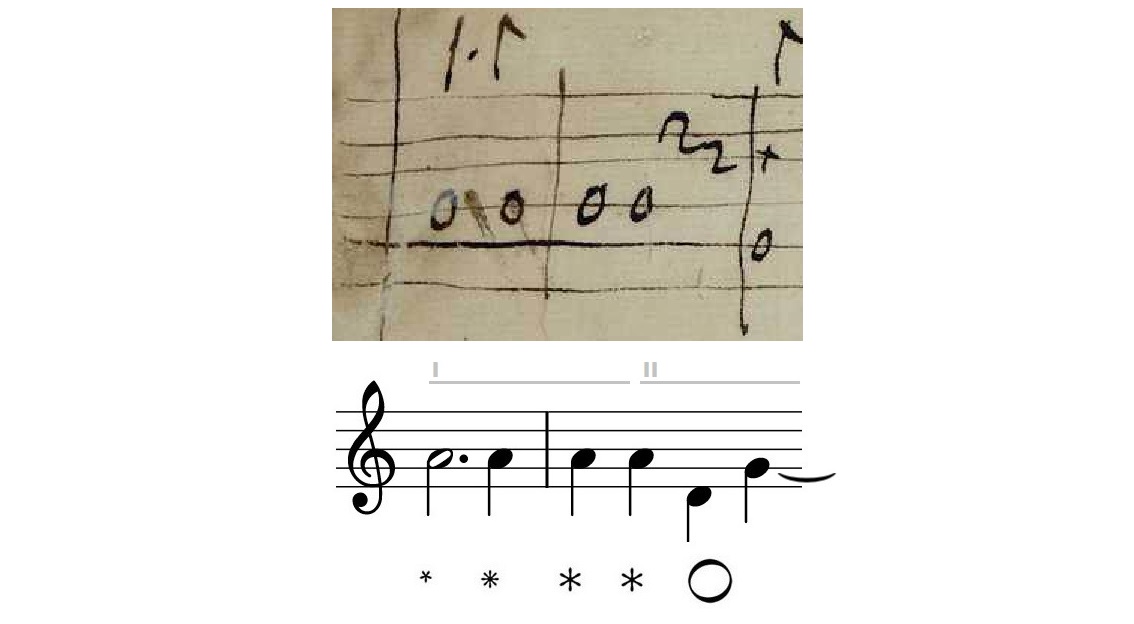

The ricercare

Manuscript

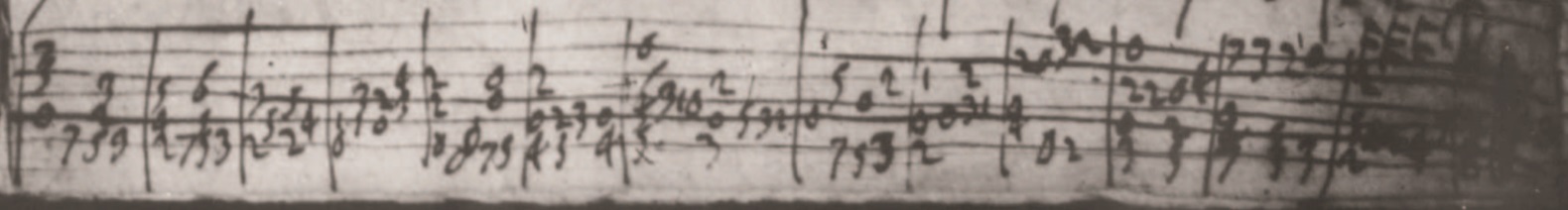

Tablature

Staff notation transcribed and transposed

Flac file

Vincenzo's counterpoint treatises were possessore Piero de Bardi. Where they handed over by Michelangelo to Bardi at Vincenzo's request?

Dinko Fabris states the manuscript of the ricercare is written in a different hand. The writing hand is not necessarily equal to the composing hand. Is every musician a composer?

Sounding the canzon subject in the low register on the notes A2 D2 G2 (as one would expext from the older Michelangelo) does not happen.

Canzon subject: Keyboard Music Before 1700 Alexander Silbiger 2004 page 250

Galileo used to stay the weekends in Venice when he lived in Padua in the years 1592 - 1610. (In juli 1609 in Venice he heard about the invention of the telescope and immediately was excited about its potential.) Did he saw or heard the organists of the San Marco at a private concert in Venice and bought some scores which triggered him to improvise and emulate on keyboard or lute?

Or did Michelangelo play with the populair canzon subject, inspired by the latest books of Terzi and Gabrieli, in 1599 and 1600 when he was in Padua? Did the contumacious melodies of the ricercare flew out his eloquent lyrical quill?

What proof or clues, if any, do we have? Did non family members have access to the manuscript? What story does this sheet of paper tell? What was the intention of the composer? Can we translate the rhetoric of the ricercare into words?

Frontespizio Carta: 1r

Galilei Vincenzio Juniore musica

Indice Carta: 2r

Musica diversa di Vincenzio Galilei Juniore

Possessore Vincenzo Galilei

Archives of the Scientific Revolution by Michael Cyril William Hunter 1998

Two days after Galileo's death his son Vincenzo exhorted Viviani to take care of a chest in which his father's manuscripts were kept safe. Most of Galileo's papers and writings were left in the hands of his son. After Vincenzo's death in 1649 these papers were passed by his widow Sestilia Bocchineri to Viviani.

Plans for formation of a Galilean Collection merged into an project. Viviani had set himself to have all Galileo's works reprint in folio form, including suspect and prohibited material.

Definitive ordering of the material took place in the second decade of the 19th century. Favaro declared the 20 editions of Galileo really complete in 1909.

Il secondo libro dei madrigali a cinque voci.

Carta 3r & 31 v Constanzo Porta

Il terzo & quarto libro

Carta 17v & 23r Pietro Luinej

Can we distract from the titles of the madrigals by Pietro Luinej a preference for Petrarch's poetry?

Petrarca Galileo's library contained three titles and five editions. Galileo's reading by Crystal Hall 2013

Constanzo Porta 1529 - 1601 had studied with Adrian Willaert and was a close friend of Claudio Merulo. He was highly esteemed for his art and as a teacher & spent his final years in Padua (were Galileo and Michelangelo lived).

Why did the scribe choose these compositions to put into reverse score? Who is the scribe of the reversed scores?

Are we sure the ricercare is written in a different hand? Is it different when it looks different?

Handwriting of:

1630.12.07v Vincenzo - son of Galileo

1630.12.07r Vincenzo - son of Galileo

1631.03.11 Virginia (Maria Celeste)

1633.05.02 Vincenzo - son of Galileo

1633.06.02 Vincenzo - son of Galileo

1633.08.26v Vincenzo - son of Galileo

1633.08.26r Vincenzo - son of Galileo

1636.08.01 Alberto Cesare

A broader selection of letters

There seems to be a difference between male and female handwriting in the Galilei family: how more readable, well-kept and carefully is the handwriting of Livia Galilei - sister of Galileo and Michelangelo, Guilia Ammananti, and Virginia. Does this exclude Virginia or Mechilde as scribe of the manuscript?

The handwriting of Vincenzo - son of Galileo, looks variable.

At the end of his life Galileo's handwriting disintegrates and he became blind. Several letters dictated by Galileo are in the hand of Vincenzo.

Measure 03, 14, 24, 31, 39 & 40

No identified autograph of lute tablature by Michelangelo has survived.

Catalogue M. Horoce de Landau 1885 Florence page 522

10431 Fronimo 1568

10432 Fronimo 1581

page 273 & 274 non autografe

Dialogo 1581 engravings page 71 and 78 tables of notes

The hand-driven engraved lines in copper where as flexible and nimble as the lines drawn with a quill. It solved many problems letterpress printing techniques faced. Printers reached for a technique producing printed music that resembles manuscripts.

The many carefree breaks in Michelangelo's book at the end of the staves at a section of a bar seems to show that the etcher or the original scribe did not bother much or had an eye for the layout.

A curious case of breaks occur in the pieces of Michelangelo in the anthology by Besard: there is plenty enough space for whole measures to be written out. Can these breaks be explained by copying the breaks after an original ten stave manuscript?

In total space of 180 staves was not used in Michelangelo's book: 18 of the 58 plates could have been spared, about 3/10 of the costs for paper, printing and plates. Paper cost were ussually 70% of the total.

The empty staves of the London copy catched 5 unique pieces composed by Michelangelo and notated by Albertus Werl.

Volta page 16 measure 7 and 8 are not repeated in the style brisé part.

A hold sign is not applied. The repetition sign appears in many forms.

A side effect of working this way is that it objectifies copying exactly and suppresses own handwriting. A second hand may tell about a first.

German composers often published their music at their own expense and had a certain control in the production proces.

Michelangelo ensures us in his preface that no mistakes have been made:

"every one can be assured that I have minutely checked the whole book many times and I am certain that it is perfectly correct."

A riskful claim and the first tablature page immediately undermines his words by ending in messed up rhythm.

Two hands full of small defects and errors in his book leaves one puzzled to what extent he was involved in proofreading and correcting.

The preface could have been written, etched and approved before the tablature was engraved and the book he describes meticulously checking over and over again might have been the original manuscript.

The loose calligraphy of dedication and preface also suggests that the engraver was not a determined perfectionist.

Striking anomalies occur in Volta 45 Primo libro 1620 measure 2 course 2 capital A and measure 16 course 6 second d has a hybrid character. Is this the first page the engraver made under supervision of Michelangelo?

A Galileo forgery 2014

Instead of further comparing handwriting and jumping to conclusions based on similarities and differences, let’s broaden our view to some features of the ricercare.

The solitary bass notes D2 8th course measure 17 seems to come out of nowhere.

What is this string marking?

The appendice: Gagliarde ed arie di Autori diversi Libro d'intavolatura di liuto 1584 by Vincenzo Galilei

Mimmo Perufo 2008

A vertical line connects uninterrupted nine of the ten staves. This line was probably the first the scribe put on this sheet, presumably thinking there will be ample space to write the whole piece down.

When this turned out to be a problematic case the solution was shrinking of the handwriting (in opposition to the musical development wherein the subject is augmented to the max).

Applying the fontsize of stave ten to the whole piece means that only eight staves would have been needed.

The horizontal lines deflect downward as a right hand tends to do. A ruler or rastrum was not used.

Measure 20 some wrong notes have been removed by damaging the paper. A sortlike case can be found on page 1 Libro for lute 1584 by Vincenco Galilei.

At the end of stave four several events occur: collision with the end of the page, (and because of that?:) the missing of a bar line, shrinking of the font and wrong notes.

Halfway stave eight the writing broadens and crashes at the end when again something wrong was written & an orbital knot was penned to erase.

When we take a look at the other side of the sheet we can decipher a bit which notes (s)he penned under the knot. Maybe the scribe didn't want to break a bar at the end of a stave and realised to late the lengthy bar could not fit entirely.

Ink has corroded three digits in measure 69.

From a compositorical point of view this is misleading. Here a composer is at work who is in control and exactly knows what he or she is doing.

The term ricercare is not written in manuscript.

Approaching the piece with the toolbox of a fugue is legitimized by the continued polyphone working with the same subject throughout the entire length of the piece and the usage of stretti and augmentation.

A tonal rather than a modal approach can be based on Vincenzo's late writings and compositions.

The subject of the three voiced ricercare is a rhythmic figure – a knocking motive: hello, here I am! – followed by a fifth downwards and a fourth upwards.

The fanfara character of the theme makes it suitable for a performance by wind instruments directed by Cesare Bendinelli.

The exploration of open strings is a central device in the development of the music.

By contrast dramatic use of alternative positioning is applied. The most significant example is in measure 91 fifth course seventh position G3 (at the beginning of stave ten in the manuscript). The reason why this note is very special will be substantiated in the following.

The Aesthetic of Johann Sebastian Bach by Andre Pirro 1907 page 42 the meaning of motifs with repeated notes

Bach developed the conviction that composition is a mode of thought and expression. The harmonies ought to be dictated by the mind, by the intentions of what the composer had to say.

Repeated notes are an example of physical immobility and steadfastness.

An Historical Survey of the Origins of the Circle: Music and Theory by Jamie L. Henke 1997 Earliest theoretic reference to harmonic circles by descending fifth or ascending fourth can be found in Kircher.

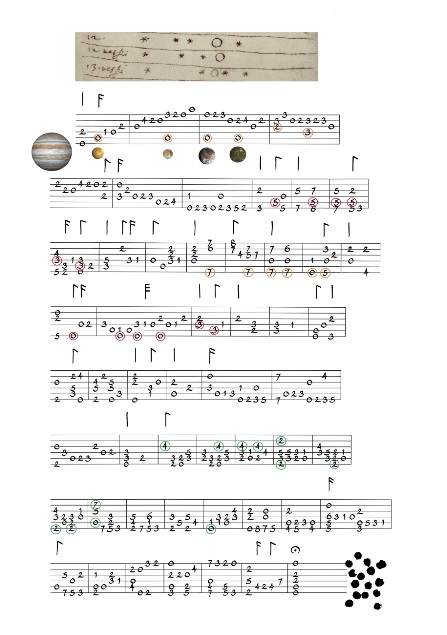

Galileo’s telescope:

1609 3-powered; 8x

1610 14x; 20x; 21x; 30x

It consists of two opposite parts, together impersonating Galileo's mumbled mythical oneliner: "and yet it moves".

A fugue subject is often not in itself a melodic sealed unit; the first melody usually only closes off as the second voice has already begun.

One of the features of the ricercare is the transformation of the subject melody from not yet completed in the exposition, to closed in itself in the coda.

The metamorphose of the function of the notes of the subject is a common thread in the musical story of the ricercare. One of the ways in which this change is implemented is by augmentation. As if we are looking through a telescope and the concept of what we see changes before our eyes.

The subject includes a remarkable overall tonal plan for the 104 measures the ricercare endures.

The letters of the name Galilei can be made to sound as a style brisé motiv in lute tablature and has a very modern nature.

BWV 870 - 893

Page 5: plagal exposition of Bach in a fugue with repeated notes.

Page 10: a trice-repeated pitch and a rising consonant fourth: the canzona motif from the late middle ages.

The classical cadence William Caplin 2004 "We should banish the plagal cadence from theoretical writings."

BWV 874 Luke Dahn “Fixing” Bach’s D Major Fugue from WTC2, BWV 874:

"The opening X motive implies G major more than it does D major."

"... results in an ambiguity of tonal center. "

The instrumental canzona arose directly from the chanson, many were edited for lute. The opening motif of a canzona consisted of one long and two short notes of identical pitch.

In northern Italy outside Venice the canzona was the chief instrumental genre from 1580 to 1620. Venetian instrumental music from Gabrieli to Vivaldi - Elenanor Selfridge-Field 1994 page 116

Andrea Gabrieli (1532-1585 Venice) wrote keyboard canzonas that are intensely polyphonic and considered as precursors of the fugue.

Between 1562 and 1565 Andrea Gabrieli was in Germany and worked as an organist at the Kapelle in Munich with Orlando di Lasso. His nephew the lutenist Giovanni Gabrieli followed him to Munich.

Canzona Ariosa Il terzo Libro di Ricerari 1596 Venezia This organ composition is Gabrieli at its best and looks like a primary source of inspiration for the composer of the ricercare.

Vincenzo - son of Galileo, owner of the ricercare manuscript, a poet with an inventive mind, his poetry rooted in renaissance models, an artist with a love for extreme ingenious organization, grounded in musical theory, played lute & it sounded as organ pipes. Was the comparison Viviani made with an organ trickered by hearing Vincenzo many times improvising on a lute exploring organ scores?

An Historical Survey of the Origins of the Circle: Music and Theory by Jamie L. Henke 1997 At times entire works of Gabrieli are based on circle progressions. He was the first to use circle progression to target a specific pitch.

Vincenzo Galilei and Andrea Gabrieli both composed a cycle of ricercares through the 12 degrees of the chromatic scale.

The Order of Things: A reappraissal of Vincenzo Galilei's Two Fronimo Dialogues by Peter Argondizza Fronimo 1568 and Fronimo 1584 show a shift from 8 mode to 12 mode order.

Intavolatura di liutto 1593 The canzon motif of Andrea Gabrieli in Giovanni Antonio Terzi

We can turn this around and see what Bach did with the related subject based on the canzona motive in fugue number 5 of Das Wohltemperierte Klavier II.

What devices did the composer ought to apply according to Bach in this piece?

The most remarkable feature of this fugue is the plagal exposition. The exposition of the ricercare can also be experienced as plagal. In this plagal exposition the progression is V-I-V in the key of D and has the same sounds as I-IV-I in the key of G.

The keys are heard differently and one can choose to hear it either way. Who has the final word? Listen to the music and you can hear arguments for both modes.

If there is one thing that roots the ricercare in the 16th century it is the plagal exposition. Is that a clue for the date of composition? Bach used it in the 18th century.

To reuse Alfred Einstein's description of some of Bach's duets: "This is only one of many of those mysterious cases in which Bach seemed to revert to the sixteenth century, without our being able to adduce philological proof that he knew music which by his time had long reposed in the sepulchres of oblivion."

Bach's nephew Johan Nicolaus Bach intended to revive the declining interest in the lute by providing the instrument with keys. The easy-to-play luteharpsichord could deceive the best lute players with its sound. Is that deceitful sound an indication for its tuning?

In 1720, the year he composed the first book of The Well-Tempered clavier, Johann Sebastian Bach obtained a luteclavichord. In 1740, the year he started his second book of The Well-Tempered clavier he obtained a new luteclavichord, this time built on his instructions.

Bach could tune a harpsichord at lightning speed. He was very reserved against experiments with different forms of tuning. It is possible that in 1720 the luteharpsichord showed him a way to equal temperament and urged him to rigorously implement the design he had devised for his inventions and sinfonia's.

The luteclavichord would travel into the dark space of history and oblivion.

A clue for the key of the ricercare, although not decisive, is the final chord.

Vincenzo Galilei, father of Galileo and Michelangelo, had contended that the designated mode of a modern polyphonic piece could only be distinguished through the last note in the bass.

The reproduction of the manuscript in the paper of Dinko Fabris is not as crisp as one would wish. The final chord in the last measure is obscured in darkness & the last readable final chord is D in stead of G:

The music of chance is here playing with the core of the concept of the composer:

it is not clear what is the main key of the composition and the final answer / word / chord / note in the bass is in the realm of dark space.

A difference with regular modulation to a closely related key is that there is no turning back, it is final. We have experienced a tonal shift from one centre to a new one.

Classifying the harmonics with certainty in this bitonal constellation is impossible. The perspective of the observer directs the observations.

The question in which key the music is composed can only be answered after viewing the whole piece, after all arguments have been weighed and then one has to choose or to conclude that both are an option. Considered this way the ricercare is a rhetorical discourse without a final answer.

What does it mean when a piece of music is not structured on a single mode? Why did Bach and Galilei emulate on a canzona theme explored in a modal mixture and disrupted unity?

Art is about making up, applying and breaking rules and it is entrusted to the French chanson as is is to the Lithuanian sutartinės to not care about how things should be done. Like the rule that there should be modal unity in music.

Harmony, once considered the master, becomes the servant of the text, and the text the master of the harmony.

The Language of the Modes: Studies in the History of Polyphonic Modality by Frans Wiering 2013

Tonal Structures for Early Music by Frans Wiering 2000: the integrated whole of a mode was an intellectual abstraction.

Madrigalism vividly illustrates a word or phrase's literal meaning.

Guilio Cesare expands on modal irregularities and mixture of modes. He cites examples of the occurrence of more than one mode in a number of Gregorian chants and compositions by Josquin Desprez, Allessandro Striggio, Adriano Willaert and Cipriano de Rore. The Monteverdi brothers applied different modes in one composition to almost equal force. Claudio honors, reveres and praises both prima and seconda pratica.

Theoretical writing about music is something different as composing. When a theory does not match practice, it still can be clarifying because of its formulated presumed guiding axioms.

Verbalizing legitimation for the new way of composing fuelled easy to understand inspired figurative correspondence-thinking: for example when water is involved, the notes moves in waves.

Easy to understand but nonetheless multi-interpretable, which deepens its artistic meaning but blurs its concepts, still challenging its listeners.

Grandscale word-painting in music, instead of incidentally or accidentally, was a novelty. Its usage could be annoying silly simplistic or impressive profound simple.

He wrote a remarkable metaphor about intervals in his Dialogue on music in 1581:

Similar laconically demonstrated acceptance of Copernicus's theory can be found in the essay An Apology for Raymond Sebond written by his contemporary Michel de Montaigne 1533 - 1592

It is not the reflected platonic essences that make this sentence outstanding. It is the heliocentric metaphor and the laconic, natural tone wherein it is voiced by this sometimes more quarrelsome man. Intervals function as planets who revolve around the sun.

Planets are called stars (stelle) - as Galileo appointed the moons of Jupiter.

Seen through the glass of this metaphor a music score transforms into a star map. Hymne to the Sun could be an alternative title for the ricercare, inspired on familiar metaphorical roots.

Bardi: "Non ne dubitate punto; imperoche i semplici molte volte nel leggere alcuno libro di qual si voglia facultà, credono (per la poca esperienza) che quelle cose non si trouino altroue che in quello; le quali i piu delle volte sono scritte in molti, le migliaia de gli anni auanti.

Simple quotes Vincenzo Galilei 1581

The Discovery of Jupiter's Satellite Made by Gan De 2000 years Before Galileo by Xi Zezong Chinese Physics 1981. A moon of Jupiter was discovered in 364 BCE.

Bardi: “Don’t doubt that at all, because simpletons often believe that what they read in a book in whatever discipline – owing to their limited experience – is not found in any other book, whereas it is written in many books thousands of years earlier."

Simpletons (semplici in Italian) have a voice in the doppelganger and layman Simplicio in the Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems.

The word semplici is used 96 times in Vincenzo's Dialogo (providing enough quotations to accommodate the 96 variations a canto of his 100 part romanesca).

Preoccupation with simpleness was hammered into his sons experience.

Vincenzo's son Galileo would found out that putting words into the mouth of a simpleton can cause critical problems.

MS. Gal. 49. fols 4r & 5r

Four moons orbiting - visualised in a subject.

(& an swept ink drop impersonating a passing meteor with tail)

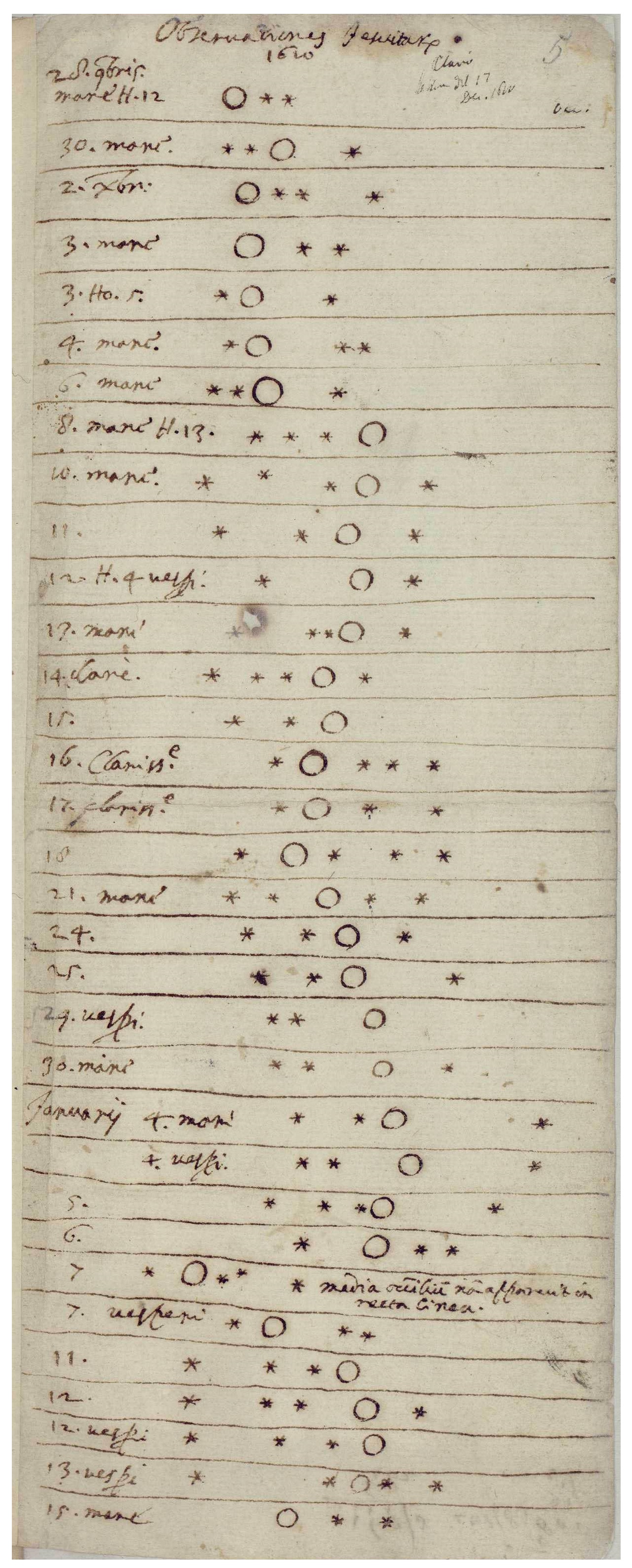

Galileo's copy of Observatione Jesuitare 28 november 1610 - 15 january 1611.

The horizontal lines tend to bend downwards. Fire and the rhythm of the music of chance burnt a hole in this sheet in roughly the same area as is the hole in the ricercare manuscript.

1611 january

Left: Galileo's observations

Right: Jesuits.

Galileo had turned his telescope on Jupiter for the first time on the 7th of january 1610. Several nights he saw three moons. Then another moon appeared on the 13th of january 1610.

Galileo didn't draw the Jupiter's in a straight line under each other: the centre seems to move - instead of the moons.

For Galileo it sometimes appeared Jupiter had not moved to the west but rather to the east.

Part II measure 2 in tablature - the numbers two on courses five and four - have the shape of a wave. The Jupiters in Galileo's notes move in a vertical wave.

Some nights it was clouded. Some bright nights he made two notes - his observations separated by a couple of hours. How did Galileo spend his time in the late hours in between, his mind focused on his notes and the things he saw and figuring out what they mean and how they move? Did he pluck some strings thinking about strange things, pinning Jupiter?

Pin Jupiter and the moons starts to orbit on paper.

History tells he figured it out how they move on the night of the 15th of january 1610. For eight puzzling nights he had thought it was Jupiter moving & not being at the centre.

In traditional cosmology there was only one centre of motion. With the moons performing their revolutions around Jupiter there were now at least two centres of motion in the universe, the Earth or Sun and Jupiter.

Two months later he published his findings, which made him famous overnight.

Michelangelo witnessed Galileo taking notes of his observations in january 1611. He and his family were in Padua and Venice from 10 january till 01 february 1611. It was Galileo first acquaintance with Anna Chiara and 6 months old Vincenzo.

Part of their conversations would likely have been about the events exactly one year before at exact the same spot.

Jupiter's moons offered a paradigm shift not easily accepted. Galileo provided many with telescopes to confirm his observations and emphasized that his data agreed with the Jesuits.

Counting unit: quarter notes starting in

measure 01: A 3 1 1 1

measure 04: D 3 1 1 1

measure 08: A 3 1 1 1

measure 12: D 3 1 2

measure 22: D 3 1 2 2

measure 26: A 3 2 2

measure 27: D 3 2 2 2

measure 36: D 4 2 2 2

measure 42: G 1 1 2 2

measure 47: D 2 1 2 2

measure 53: D 5 2 2 2

measure 60: G 4 2 2 2

measure 66: D 4 2 2 2

measure 71: G 3 1 1 1

measure 85: A 6 2 2 2

measure 88: A 6 2 2 2

To the left: the length of the augmented first four notes of the subject compared to each other. The proportions and relationships change.

Eight times the subject starts on D & eight times the subject starts on A or G.

Vincenzo's son occupied himself intensively with the heliocentric worldview. Here an illustration from a manuscript of Galileo's book from 1632. Sunspots and rays regrouped into a face, somewhat like a tongue in cheek lion. Based on this drawing one could assume that Kepler's ellipses did find his way in Galileo's concepts of our solar system.

Vincenzo - father of Galileo and Michelangelo, seems to have accepted and laconic proclaimed the heliocentric system of Copernicus and the ricercare which is at the centre of this article seems to illustrate the shift to such a view and even gamesome refers to Galileo’s discoveries of Jupiter’s moons.

The subject is augmented & at the end gives space to the two voiced counterpoint to ad arguments for the subject to be final in itself.

Part II of the subject - the circle of harmonics - is slowed down by the augmentation & is harmonic coming to a stand in measure 88 - 91.

The most dramatic use of alternative positioning on the neck of the lute is applied to this very special note. For a luteplayer it takes much concentration and experience to sound a note eloquent and melodious in this position, high up the neck in the low register. It connects difficult physical effort with a big mental step. The conceptual duration of this note passes far and far beyond its actual sounding and written notation: it could go on for ever.

Extremely ingenious constructed the ricercare is, Yoda would say.

Among professional astronomers (compliers of horoscopes) and almanac makers the heliocentric system was not so much a revolutionary cosmologic model, but rather the basis of assessment for improved calculations.

1. (fl) Anno Christi navitatis 1556 die Septimo mensis Decembris Venetiis L 10L (TP) P. Josephii Zarlinii. Giuseppe Zarlino (†1590), choirmaster at the San Marco cathedral, distinguished music theoretician, possessor of a large library and author of some small tracts on calendrical problems.

No annotations."

How can this author of calendrical problems help us any further?

- The Copernicus owned by Zarlino

- Prophecies by Licinio Fulgenzio Nej

How did he come to his opinion? We should take a step deeper into time.

Singer-songwriters, the Lute, and the Stile Nuovo by John Griffiths 2015 "Ficino's performance style appears to have been transmitted as intangible legend rather than in material form."

Ficino translated the 2nd century CE Orphic Hymns and was famous for singing them while improvising on the lute.

The Camerata Fiorentina, a group of musicians, poets, humanists and scientist, gathered under the protection of Vincenzo’s patron Bardi in the years 1573-87 and experienced intellectual pleasure of challenging new ideas.

Diversarum speculationum mathematicarum et physicarum liber by Giovanni Benedetti 1585

Galileo's Pisan studies in science and philosophy by William A. Wallace 1998

Quantifying Music by H.F. Cohen 1984

Benedetti was interested in the science of music and published correspondence (explaining consonance and dissonance in physical terms) with Cypriano de Rore - the favorite composer of Vincenzo Galilei. Girolamo Mei, who provided the intellectual impetus to the Camerate, had followed some much appreciated university courses by Benedetti in Rome.

Benedetti was "court mathematician and philosopher": a title which was like music to Galileo's ears. It is thought that Galileo derived his initial theory of the speed of a freely falling body from his reading of Benedetti's works. The core of Galileo's musical discourse was the combination of concepts of Giovanni Benedetti and Vincenzo Galilei.

Concepts in which predictions play a role are horoscopes.

A task of Galileo as a mathematician at Padua University was teaching medical students how to cast a horoscope.

Unlike his predecessors, Galileo did not include the subject of astrology in his courses. Sara Bonechi - How they make me suffer - Florence 2008 page 21

In 1610 Rasi was sentenced in Florence to be hanged, drawn, and quartered (just to make sure, in line with classic renaissance modelling and the fate of the murderer of the French King Henry IV in the same year - who before being drawn and quartered was scalded with burning sulphur, molten lead and boiling oil and resin, his flesh then being torn by pincers).

In 1612 the complete and alive but sick Rasi visited Michelangelo in Munich and as good friends do, they talked about fate and facts of life.

Michelangelo suggested Rasi to request Galileo to make his horoscope, which Galileo did.

Year 1664 does not exactly contribute to confidence in the precision of this exercise.

The outcome was a brief summary of the biography that Claude had compiled himself and it does seems to proof cliche moral verdicts are written in the stars.

This was done long after the facts, which a little detracts to the amazingness of Antionette's performance.

Galileo's money problems were over. He moved to Florence but would later look back at his Paduan days as his happy years.

Owen Gingerich 2004 chapter 12

800 of Kepler's horoscopes have been preserved.

In 1595 amidst the little ice-age Kepler had succes rightly predicting coming winter would be cold.

Johannes Kepler's interest in Practical Music Earthly Music and Cosmic Harmony Peter Pesic - ISCM Issues Volume 11 2005 No.1

Briefe 783 Kepler to M. Wacker von Wackenfels 1618

Band 21 2009 Kepler's handwritten commends on Vincenzo Galilei's Dialogo

He read three quarters of the book, so he came into contact with Vincenzo's heliocentric metaphor. Especially the first part was read with the greatest attention.

It was fresh on his mind when he worked on Harmonice Mundi and Vincenzo Galilei is cited many times.

The music had to be ingenious.

Contemporaries of his age:

1571 - 1630 Johannes Kepler

1575 - 1631 Michelangelo Galilei

Based on his reading of Vincenzo's Dialogo modern composers were for Kepler the ones representing the old-fashioned polyphonic style.

A typical case of over-interpretation by an obsessed layman focussing on something random, instead of an essence?

Or should we qualify the drawn correspondences between this motet and the world as meaningful poetry - not as much as poetry by di Lasso but as Kepler's?

In me transierunt - Orlando di Lasso

Pages 6 & 7

Il secondo libro Intabolatura di liuto di Melchior Neysidler 1566

Joachim Burmeister's Musica poetica 1606 contains a minutely detailed analysis of the

motet. It is widely regarded as the first full-scale analysis of a piece of music.

Music Analysis in the Nineteenth Century by Ian Bent 1994

For a clear analysis of Burmeister's analysis see Claude V. Palisca Studies in the history of Italian music and music theory 1993

Burmeister dissects and describes, in yet another application of correspondence thinking, equating musical techniques and rhetorical figures, but ignores any common thread.

His comparisons makes it possible to speak about structures of a composition with the well-assorted toolbox of the rethoric.

Kepler adored Orlando di Lasso, wishing he was alive to teach him how to tune a clavichord.

Compare Kepler's citation of the start of the motet In me transierunt and the lament measure 85 & 86 of the ricercare:

The harmonies of a moving and singing earth redolent of human misery are incorporated in the ricercare at its dramatic peak.

In his book Kepler describes how the earth wanders around its G string, whereupon Jupiter is marking the D string with its perhelial movement.

Of course harmonic similarities can be chance.

Therewith it seems likely this is a dead-end way on the road to understand what is happening in the ricercare.

It is time to look into a different direction and follow a different trail, that of a soldier, who was a real philosopher, widely regarded as the father of modern philosophy.

In 1633 Galileo was condemned for ascerting his cosmological findings as fact. The news reached Descartes at the moment he had just finsihed his cosmology book, titled Le Monde - The World, also establishing the heliocentric system as fact. Terrified by Galileo's fate and afraid to make Jesuits his enemies, while he needed them to teach his method, he decided not to publish.

Using the network of the Jesuits he ended up as a fighting man in the service of Duke Maximilian I of Bavaria just in time to participate in the beginnings of the Thirty Years War.

The start of the war that gave Michelangelo the opportunity to compile his book about The flight of Swallows brought Descartes to the battle of the White Mountain, joining the staff of the Duke of Bavaria and accompanying his army on its campaing. Both serving the same Duke.

Others say that every aspect of his method is already there.

The army had taken winter quarters. Joining the army & seeing something of the world meant being lodged in with a town inhabitant, living a gentle, comfortable life.

Most of all it meant waiting. He rarely left the house, spending his time in Bayern reading and contemplating. Whhich books were hot from the press in 1619?

Descartes was familiar with Kepler's books (he did use the new math described in Kepler's Harmonice) but made little explicit reference to him. A reference to On the Six-Cornered Snowflake being the exception. Correspondence 127 Descartes to Mersenne March 1630

The star-shaped snow constituted an inexplicable miracle and admitting the impossibility of a rational explication suggests the programmed failure of Descartes' project. Winter Facets: Traces and Tropes of the Cold 2007 Andrea Dortmann page 78

The Snowflake was testing ground for his Discours de la Methode 1637, fundamentally demonstrating the hypothetical method of mechanical philosophy.

He had several dreams. In his last dream he saw two books: a dictionary which appeared to be of little interest and use and a compendium of poetry which appeared to be a union of philosophy and wisdom.

In his college days the thing that made the most impression on Descartes was his encounter with Galileo's ideas in 1610.

In 1610 the King of France was murdered.

While the French Court wrote secretly to Galileo to discover a celestial body to which the name of Henry could be attached, the heart of the King was taken to be enshrined at the College Chapel at La Flèche.

A year after the chalice with the heart arrived essays and poems were displayed at a ceremony held at the College. Fifteen year old Réne Descartes is a likely (très probable) candidate to be the author of the Sonnet sur la mort du roy.

The poem links Galileo's thrilling discovery of four previously unknown heavenly bodies moving around Jupiter and the journey through space of the soul of the French King Henry IV.

Cosmopolis The Hidden Agenda of Modernity Stephen Toulmin 1990 page 60

The poems marked the union of philosophy with wisdom.

To his conviction the words of poets are fuller of meaning and better expressed because of the nature of inspiration and the might of phantasy.

What is the point of this story for our quest?

The loose associations, connections and analogies that artists can make, so different from the by various requirements restricted science, can express insights which form a valuable resource to understanding.

The connections of the concepts of the heliocentric view with the ricercare or the analogies between Jupiter's moons and the manuscript aren't scientific.

But they might be in serious dialogue with the intentions and rhetoric of the composer.

The theme as Galileo's punchline, the score as starmap, the harmonic constellation with two centers: these were features that struck me after hearing the music and seeing the tablature.

This paper set these associations in a conceptual and historical framework, clarifying a communicated core or a projection (the distinction depends on the perspective).

It documents many (different) insights of many people. What they deem, think, regard, count, reckon, believe, credit, regard, take for, repute, reject, accept, consider, submit and why.

Marsilio Ficino Firenze 1493

“Le muse, infatti, con Apollo non discutono, ma cantano.”

Something deep and meaningful is touched in the ricercare. That is the accomplishment of a gift. Art in the hands of a gifted composer will spread tone at what he is capable of.

Abstract concepts can resonate in the eye and ear of the beholder as we speak of the ricercare which is at the heart of this article and the music of chance will sing along.

There are many stars spinning around in this constellation and pinning the ricercare to one Galilei is speculative.

I have not yet got to the bottom of this. Nothing is certain but hypothetically there are some arguments that have been added in this article for this or for that.

2018