|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Back to B

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Foundation Book

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In which the right way to thoroughly learn all kinds of

scriptures is clearly explained, and artfully mixed and taught by the

subdivision of figures and letters.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Illuminated by Jan van den Velde, van Antwerp, Anno 1605.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General instruction of this book

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thorough

information to make a good quill

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Many have often marvelled, seeing with what liberty and

power some of my strokes (almost quite against its nature and power)

have been drawn, pushed and pulled. But if they have my quill, and my

hand to direct it, and also my eyes to guide the way, they would know

by experience that they have a strong quill in their own hands, and

some would not believe it is possible what I achieve with her (without

boasting) courage.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Therefore, before I come to the instruction of the character

of letters, I intend to deal with a little of the nature of the quill,

in which to learn almost all that is involved in writing all kinds of alphabets.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

And though there is no one, however little experienced in

writing, who does not know how to cut a quill, yet I think that the

majority do not know the particulars to be used in cutting the quill,

in order to write with more lightness and grace.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I will explain my manner, and would much rather be blamed

for elaboration, than be accused of negligence, and not of soundness,

on account of length and other matters of writing, and be able to

prepare the tools for the quill-art of which I profess.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

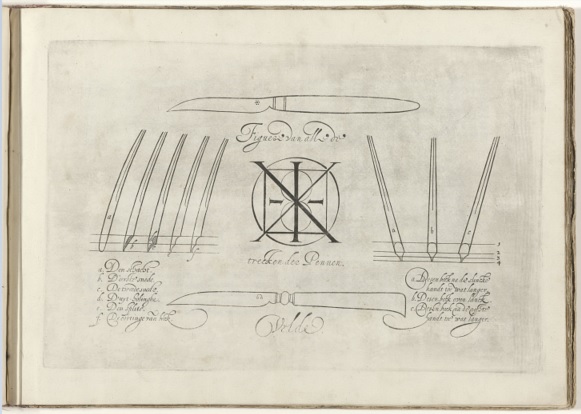

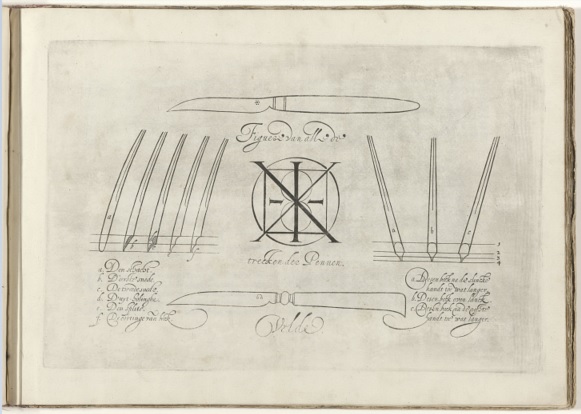

First of all it is necessary (as is also the case with all artists and other craftsmen) to have good tools. Whoever

wants to describe the sheet will have to do with a good penknife, not

too wide, nor too thick, but with a subtle straight cut, the point

slightly curved like a hawk's beak, not too short, and the handle

somewhat stiff in the hand, to be able so much more to act skillfully.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Then,

to cut a good quill, one shall hold the shaft with two fingers, namely,

with the thumb and the forefinger of the left hand, resting it on the

third, and the penknife in the right hand up to an inch wide from the

tip because you can cut more confidently that way.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Then

you will hold the shaft of the feather with the front part of the blade, with the

thumb of the right hand resting on the fourth and last finger of the

left hand.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Then

work on the shaft. Let your right hand thumb rest on the 4th and 5th

finger of your left hand and open the quill with one long cut along its

belly. After that two cuts on both sides towards the beak. Keep the

beak of de quill broad. Then turn the quill with the belly down and

with the point of the knife at the broad tip, make the slit by pushing

with the point. If the slit isn't long enough, push it with the nail of

your right thumb a bit further open. others

use the hilt of the penknife or some other shank, but that does not

work well.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Then

you shall straighten the sides of the beak, thinning them and

sharpening them, until you see that you are able to give the last edge:

the opening near the beak you shall reduce but half, and keep it so

long like the beak, which I make as broad and narrow as the letters I

intend to write.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Then

cut the quill evenly on both sides of the slit and cut the broad beak

to required size. If the shaft is too hard or stiff: make the slit a

bit longer. If the shaft is too soft, make it shorter, but always try

the quill first.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Remains

the necessary and most important, which is to shorten the beak, best to

do that on the nail of your left thumb, with the rounded side up, a

small cut towards the point to make the material a little thinner, so

that your thin lines will be so much finer and crispier.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

You

must then cut off the point on the thumb, you will then hold the

penknife with the cut on the back of the beak a little slanted, and cut

from top to bottom to the point, to make binding the letters together

as much cleaner as possible and make it more subtle.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Then take the penknife again to cut the tip of the beak straight off, and smooth it out on both sides.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

You

make the right angle a bit shorter and a bit thinner or smaller than

the left side, a bit shorter I say, because in order to hold the pen

properly one has to bend the hand a little bit to the right side, and a

bit thinner and smaller, because the ink then flows all the better.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

left side is a bit coarser, because it has to endure more, caused by

the fact that the pen is usually always written from the left side.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Now

to admonish you that it should be cut so sharply that there should be

no raggedness or roughness, I think it unnecessary, since you may judge

for yourself that good instruments are always the most able to help you

with that.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Now

that the way of cutting the pen properly has been given, you should

also know that there are all kinds of pens: first, one that is even

from the beak and of equal length, and second, two others with an odd beak and

uneven, which I should here, as well as the way of the penknife, would

like to point out in many figures, the better to reveal to everyone my

teachings.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a. this beak is towards the left a bit longer

b. this beak is left and right the same

c. this beak is towards the right a bit longer

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

For which type of letters these three types of quills will be used for.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Now

to clarify for what purpose I use these three kinds of pens, it should

be known that I use the smooth pen for all sorts of coarse erect

Fracture writings, Textur writings, Bastard letters, large and small,

and then all other fixed square and round letters, to write

inscriptions or some fencing and delightful spells.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

two unequals I usually use for current affairs, such as High German and

Dutch, the first because the beak against the right hand is longer than

the left one, I usually use to write a backhand, and the other, because

the beak of the left hand is longer than the right one, for a forward

hand, and also for writing an Italian hand, except that then the mouth

must be a little longer and sharper because of the long subtlety and

roundness of those letters, as also the mouth of the pen for a Dutch or

High German handwriting, which should be shorter, because the letters

are much shorter and bolder.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A

wider use is also another way of pens, when I desire to write a round

running hand, whose mouth, after I have cut off the smooth nib, I make

a little roundish, on both sides the corners are slightly reduced, but

not so much as to make her lose the flatness, just a little bit of the

edge, because it rolls better then, and this is without a doubt the one

that gives the most speed, because anything round has to run a lot.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I

also use a similar pen to draw my lines, but take a shaft that is a bit

stiff, make it a bit longer, and the split too, so that the ink will

follow a bit more slowly and with steps.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

And

to prevent it from being obtrusive and sprinkling (you won't see or

encounter that much in my writing) so I'm running it up against the

back a little heeled, like a ship tacking sweetly, so that it's all the

sweeter across the paper floats, for wanting to sail gliding, or partly

against the back, one can hardly prevent her from struggling and the

lines falling out wholly impure, which equality and purity I hold to be

great art and science, as being one of the courage and special touches

that may bring a masterful writer to fame.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

And

in order to make the lovers and doers of pens discover my manner still

more widely, I was willing to let them know how I use my strength

(which I do not pride myself on except that I received it by the grace

of God) in the actions of the pen exceptionally on a large sheet.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

So I take one of the stiffest or hardest shafts, which

you soak in a little water, to be ready in my inkwell, to make it a

little softer and gentler, that it might be more able to draw its lines

that way and to bend, and to endure the heaviness, for though it be

slackened a little by water or by ink, yet by its features it remains

steadfast, when I have applied the softening, which others that are

softer or slacker do not power. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

For, as soon as the beak has taken the ink, they will

immediately succumb under the hand, whence it follows that the features

so pious and stout will not fall from such pens. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I also take for this purpose an ink that flows and

runs, without putting any cotton in it, so that the hairs in the pen

will not hinder the writing pure and clean. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I

also prefer smooth and strongly glued paper for this purpose, for the

sake of which the pen itself advances more lightly, and if I see that

my ink runs too much, I throw a little bit of gum into my inkwell to

bind it a little more, which I also do when I want to write a quiet or

slow hand.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

If

not, take a kind of paper which is a little slower, which does not like

to take the writing, unless the pen wears out too quickly, and the hand

gets tired, also because I don't write very slow, because today's

merchants, clerks, and copyists do not esteem them highly, for whom it

is enough to have before their eyes a clean and steady running letter,

without having to worry about curiosities.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Those

who must all manage perfect writting are noblemen, lawyers,

secretaries, notaries and schoolmasters, for them it is right and

foremost that they can write several common writings perfectly, in

order to be the better and more able in the service of princes and

lords, and will help the progress of various states and republics.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

How to properly grasp or hold the pen.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hitherto

I have thought of the carving and making of the pen, as well as the

variety of how to act, now it is also necessary to know how to grasp,

hold, and rule it.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I

usually hold them with three fingers, namely, with the thumb, the front

and the middle finger, in such a way that the first finger and the

thumb are equal, and the middle finger slightly outward, next to the

nails and not over it, the two nearer will follow the middle finger,

which will rest a little on the gold finger, that again on the little

finger, so that the hand rests and rests on these two, but more on the

little finger, with which I alone but touch the paper, that is to say,

from the two little phalanges upwards towards the nail, to prevent them

from touching the other fingers, which hold the pen, that they do not

prevent them from bending or moving and moving forward, after one has

quickly desires to write.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I

also keep her weight so that the top of the point corresponds to the

direction of the right shoulder, and always have the arm free up to the

elbow, leaning a little on the table with that, leaving most of the

shoulder to hang.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I

support the body with the left arm, which I place on the table to

illuminate the right, paying particular attention that the paper or

book I am writing is right in front of me, and the body is not twisted.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I

also do not close the pen too tightly between the fingers, and do not

push it too firmly on the paper, because I find that if you hold the

pen too tightly and push too much, the fingers will soon get tired.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

same is true of lying or resting too much with one's body on the table,

it prevents one from not writing skillfully, and one cannot maintain

evenness and thickness and breadth, which is the jewel of all writing.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In

short, I keep the pen in such condition that when I draw a downward

line the way of the plumb line, or a transverse trace, beginning from

the left hand to the right, or make with the purl side of the pen, that

that is always made with the flat part, that is with the width of the

nib.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Contrarily,

the different lines over oblique sides, from left to right, or from

right to left, then I take with a sharp, or rather with the edge, that

is the subtle and thin, starting with the right or left corner .

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In order to arrive at a broader explanation, I have listed the most necessary figures here.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 The straight descending line, Perpendicularis in Latin, was drawn like this with the width of the pen.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 The descending diagonal line the width of the pen, called Obliquus.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 And the other opposite line, called Diagonalis, was drawn with the edge of the pen in this way.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 Another straight transverse line drawn with the width of the pen.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 Yet another drawn half-width line from the pen.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 Made another one with the pen's cut.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 Other lines taken with a reversal.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 Some semicircular lines.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 Some extended semicircular lines.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10 Other curved semicircular lines.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11 A whole round line.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12 A braided round line.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

13 Half Falling Ovals.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14 A whole falling oval.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

15 Elongated squares.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16 Curved squares.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

17 Square diamonds.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

18 Curved diamonds.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

19 Round Points.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

These

examples of flat lines should be diligently observed by anyone who

wants to achieve the perfection of the pen, I can assure you that it

will be no small profit and advantage, and you will find that our main

writings have their origin in this, as I hope to give fuller

explanations here and later on, I advise anyone who wants to become a

professional to teach children how to write, that they build their

lines from it, if those who are beginning to learn for a handwriting

practice it for so long, until they shall be able to learn to make

letters, taking special care that they hold the pen well, and the

manner in which it shall enter in the flat and in the cut, that they

may write with a fair and steady hand, and not use wrong manners which

they are very ill to dissuade, and prevents them from learning a good

disposition of writing.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Declaration of the figures as proposed.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Before

I come to the foundations of our writings, I should first like to

clarify what is meant by the above-mentioned figures, so as to have a

more competent introduction to the teaching of letters.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The most important line, and also the most difficult, is the Perpendicularis,

which must be drawn with the flat of the pen from top right down, so

long and so short to the letter you want to write, which line should be

especially learned as being the one from which most of the letters take

its form.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Oblique and the Diagonals line, as well as the others, fall much easier and have more freedom.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

These

are drawn, one with the flat of the pen starting from the left hand to

the right going diagonally downwards, and returning from the right hand

to the left upwards.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

others who are drawn in the square figures from one corner to the other

is the one who joins letters with the edge of the pen, either from the

middle of the body from the head, or from one leg to the other of

downwards upwards, for thereby it is separating distance and width

which the letter ought to have.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

other lines, namely the transverse ones, are the ones that run right

through the letters: the first that is passed through the coarse with a

flat, the second that is passed through the midline with a semi-flat,

and the third that with the edge of the pen swept through the small

letters.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

They

are also used (with the exception of the last two) to make the head and

foot of such letters, because their nature requires it, as there are

the Roman square and round letter, the French, and our stationary

letter.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Curved and round

lines are drawn with the edge of the pen, ending without interruption

with the flat, or starting with the flat and ending with the edge.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Half and full ovals are the ones on which the Italian hand is most based.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Squares serve as feet of the Texture letter.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Diamonds as feet of the Fracture and the Bastard letter. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Points are made with a push of the pen to put on an i, and to close a whole sentence, either in the middle or at the end of the lines.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

What

more is required of this for the art-lovers, practice will teach, and

the foundations of it, as every one will attain perfect perfection

through constant study, for Not without effort.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Instruction of the square Roman letter.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Now,

in order to come from all these lines to an application to all

writings, we shall first deal with the ancient Roman letter, which

seems to have descended from the Greeks, and is thus a square letter,

which I have arranged here to make its proportions the more vivid,

positing these few figures standing above the foundation to the very

bottom of the foundation itself: namely, the Perpendicular line, the reign of lines that go straight down, the Oblique line for all that go obliquely from the left hand to the right , the Diagonal line for all those half-flat strokes that go against it from the right hand to the left, and the Transverse line that is made with half the flat pen for all lines that go across and through the middle below and above the letter.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

And the Round

line for all that fall round, which is approached with the edge of the

pen, as well as those of all other lines that are sharp, as can clearly

be seen from these figures.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Instruction of the round Roman letter. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Those

who have practiced well on the square Roman letter will therefore

easily come to know whatever form it takes from the few figures

mentioned above, and especially from the i, o, and f, which rule most

of the entire corpus of these letters. , otherwise have no difference,

except that some lines stand out under and over her corpus (that is the

body).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

And

to clarify here what I mean by its corpus, so it will be known that I

call the body of the letter that which is enclosed between two

parallels or lines, and name the members that is, the lines that rise

below and above it, which (in order to determine its proportions) I

make rise above it neither higher nor lower than once as long as its

body is large, except for the t, which must protrude above the line

only one-fourth of its height, as also in the image is displayed.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

There

are more and other Roman letters, but these two are the ones most in

use today, from which ground and foundations all others can be easily

understood and made.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Therefore

I beseech the enthusiast to content himself with these, and to practice

in the manner now most in demand, and most esteemed, when there be the

new Italian, Spanish, French, and Dutch running hands, from which I

recall intend to deal with.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spanish letter instruction.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

...

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Description of the Italian letters.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Italian writings most commonly used by modern writers are four, namely Letra Formata, Posée, Cancellaresca and Corsiva which is the youngest of them all.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Formata

is only for printing and for writing some songs or other verses, it is

the fattest and largest of them all, and is therefore written with a

fat-like pen to make its corpus strong.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I

give her almost the width of her height and make lines running out

above and below as long as her body is, and set the lines twice as wide

as she is tall, as you can see in the letter I sent to my E. Heere the

Pensionary and the Rector of our town.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Posée that is a silent or slow letter, and not dissimilar to the Formata, but that it is but a little stockier, and whose limbs or tails are taken with an inversion, unlike those of the Formata, which are blunt and straight be cut off.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Posée

I give to copy to my disciples who begin to learn to write with an

Italian hand, the most able to lay a foundation, because it is

assembled letter by letter, without tying them together, which is a bit

too heavy for the arrivals at the beginning.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cancellaresca is, in my opinion, the most delicious, and Corsiva

the most useful and handy, and so I will try to explain its qualities

and my observations a bit more broadly, to display to enthusiasts and

beginners, after which they will see their aims, to imitate as closely

as possible the script lines of such fine letters.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

For starters, you need to make sure that the letters don't lean forward or backward more like the others

and that all the protruding lines below and above project in the same

direction otherwise it would lead to confusion and disfigurement.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Its

corpus will be as long as it is wide, and the spaces between the

letters as large and wide, and the words twice as far apart as it is

wide.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

spaces between the lines shall be three times as wide as it is long, so

that the members projecting below and above do not interfere with each

other and become entangled with each other, their length being one and

a half times as long as the body.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Corsive must be much narrower, and its lines thinner and more subtle so that it can be written all the more skilfully and lightly.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I

make it once as long as it is wide, and the protruding lines twice as

long, the letters a little freer and separate from each other, and the

line width four times as wide as that length, so that the pen can so

much better give and prevent its full course that the protruding lines

(which I have called members) do not interfere with each other.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

These four lines will serve as an example for you of the four Italian letters mentioned.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

These

observations I have wished to explain, so that all who love this hand

and seek its way may have some foothold leading to the perfection of

these Royal Writings.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I

do know that some curious minds, who pay close attention to my writings

and my teachings, and search them out with great earnestness, seeking

especially to rebuke another, instead of correcting, I would ask them

first to make a good distinction to one and wanting to make another

before they criticize the temperance of my pen.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Because

even if it is true that she has deviated from my instructions here and

there and has slipped out, it will still be seen in it that there is no

confusion or disintegration to be found in it.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Poets

have their own rules, philosophers have exceptions, and painters their

ornament, so also the pen has a likeness, which through the quick hand

(like one that is very quick or lets its lines run out quietly longer)

also spreads its wings a little wider, then writes as a standing or

slow letter, because the haste one has sometimes misplaces one's foot.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

How to cut and hold the pen to write Italian letters.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Because

before here I have described little about how to cut a pen to write an

Italian letter, I thought it right before I go further to clarify how

the letters are made in particular, to describe her creation here in

more detail.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

beak will be made somewhat elongated and will not have to be hollowed

out as much as one does to write the German hand, so that the ink will

follow so much lighter, the strokes that come at the beginning or the

end of the letters can already be made with a line in a row.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I

also make the beak a bit roundish, the corners on both sides tapering

off a bit, so that it doesn't slow down on the paper but will move all

the faster.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

beak will also be cut as wide and narrow as the thickness and

narrowness of the letter one wants to write and the split as

appropriate in length, to make the quick lines that are placed under

and above the body as fat and lean after she be pushed hard or soft,

and so that one shall know to belong to her stature.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

And

thus the Italians hold the pen in a different way than we hold our own,

so I have also wanted to describe it here, in order to satisfy all

curious minds, and avoid being accused of not knowing it.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Whichever

way I think good, because one thus tenaciously writes the pen so much

lighter and more skilfully: they hold the pen only with the thumbs the

front finger, in such a way as to show the strength of the thumb next

to the first phalanx of the fore finger, which is extended to the side

of the pen, in such a way that it comes to lie next to the third and

last member.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

other three fingers will all be arranged on top of each other in

foreshortening, the middle finger partially on the gold finger, and the

gold finger on the little finger, as one can clearly see in the figures

above in the beginning of the Italian script.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Brief message and instruction how to make Italian letters each in particular.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

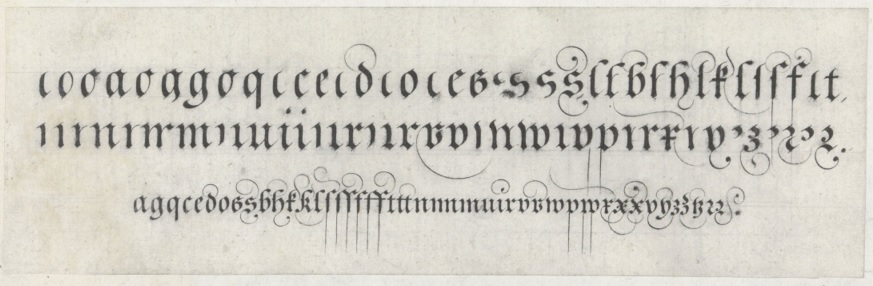

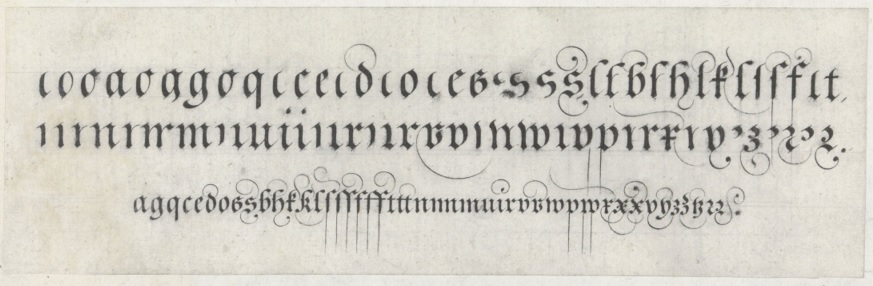

Now

to come to the teaching of the Italian hand, I shall give notice of

each letter, and what letters take the origin of another, all this

contained under three principals: o, ,i & f from which all others

spring, why I will also first clarify how to make them.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

o

|

The

o I start with the right angle of the pen, pull the thumb a little so

that the pen begins to descend to the left hand, flat down, then

turning to the right hand, before moving it across upwards, to the

beginning of the o create and close it.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Make the top and bottom equally wide, which is for the sake of her grace.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

On

which the letter o has most the whole body of the Italian hand and is

founded, as well as all the other letters, is the shape of the oval.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

i

|

The

i is made from a straight down line but is started with a small fine

line made the the edge of the pen or the side of the pen, and ends with

the right angle of the pen by making a small outline in the same way as

that of the o.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This letter also has a large share in the body, as we will prove next.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

f

|

The

f is also no less powerful, being the one from which all the members'

lines projecting below and above the body take their origin.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

She

is started with a good angle of the pen, in the manner of a little

curve line, and then reversing, I then join the line to make her head

with a little elongated stroke.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Falling

down there to the second part of her length, I draw the pen to the left

hand (which is one third) and make a little scrap at her tail or to

continue with a return to the right hand, sharply projecting, etc.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

From

what three letters, as vivid origins of all others, we can explain the

form of each letter alone, beginning from the a to the last letter of

the ABC.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a

|

The

a, the first letter of the alphabet, is made from the o and the i, and

draws the i with a straight line against the right side of the o.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

b

|

The b takes its being from the two upper parts of the f, already makes its belly in a sweep upwards in the same way as the o.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

c

|

The

c I start with a little scrap like the head of the f but not so big and

make her body even as if to make an a, and finally in the inversion I

fly the pen sharply upwards.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

d

|

The

d is also made partly from the o and from the f, I start as if I want

to make an a and come from diagonally above descending downwards as if

I were thinking of making an l, and end like an a.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

e

|

The

e I start with the right corner of the pen and turn it to the left hand

to make the head, turn the pen down into the flat and end her body as

the c.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

f

|

The

f has no other difference from the f than the little line which I draw

with the edge of the pen right through the body itself, sometimes its

shape is changed by the different heads and tails given to it, which

are three.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

first retains its shape from the f, the second has made the straight

from a bicycle kick to the right hand with the flat of the pen softly

disappearing, the third has the head and tail made with an inversion,

whatever lines be used with all other letters whose members protrude

above and below, such as b d h k l p q.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

They are most commonly used in running hands, as they give the most speed and are very elegant.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

g

|

The

g is made from the o and from the last two parts of the f hanging over

the top of the o's head, and draw out her tail with an upward sharp

line with a lightness to the bottom of the o

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

h

|

The

h is made in the manner of the , and has no other difference than that

its body is open at the bottom and that of the b is closed.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It is also being changed in various ways as can be seen in the foundations.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

k

|

Although

the Italians and the French do not use k, I have nevertheless also

wanted to describe its form, because one or the other, of whatever

quality it may be, must be satisfied.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

She

is made of the f, begin her head like the head of the c and come out

with the cut of the pen in the middle of her body, turn with the flat

towards the right hand going obliquely downwards, and make her street a

slightly bent, it ends with a sharp swipe with the edge of the pen.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

l

|

The l also takes its shape from the two upper parts of the f.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It

is made with a drop to the left hand and from there to the right,

ending with a small line approaching the edge of the pen that rises a

little.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

m

|

The

m is made of three legs, like the i, which are lightly tied together in

one movement without lifting the pen, floating upwards with the pen's

end over the first leg, and falling round with the pen's flat to to

make the second leg, and so also the third which I finish like the t.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

n

|

The n is made from the first and third leg of the m.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

p

|

The

p of the two lower parts of the f, part of the o, but is equal to the i

with a small line drawn at the right angle of the pen.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It is changed like the tail, as I have treated before, and the body is sometimes made of a round r.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

q

|

The

q is made from the o and the f, just like the g, and is no different

except for its tail, which comes in three forms, as I mentioned before.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

r

|

There

are two types of the r, the first is made from the n and like the i is

taken with a small line from the edge of the pen, after that is done

you will pull the pen straight down and then go up again from there to

the two parts of the body, with the right angle side of the pen to make

the head, and give a little nudge with the flat of the pen at the end.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The other r is taken from the o, namely from the upper and lower part.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I

start from the top with a bicycle kick, then with the right angle of

the oen move slightly upwards and then slant down to the left hand

until half the body, then I turn the pen in the flat back to the right

hand , and let her fly out sharply on the same side.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

s

|

The

little s is also made from the upper and lower parts of the o, but

opposite to the r, for as the r is drawn down from above to the left

hand, so in contrast this s is drawn from above with the flat from the

pen to the right hand drawn down obliquely, make her head with a small

inversion, and so going down to the right hand, turn the pen to the

left hand to make her tail, which is done with a nudge in the back of

the oen, once so big as the head is.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Two

ss are joined together, cut the first part with the edge of the pen

straight through her body upwards to engage the head of the second,

which is also done with an inversion through the body itself.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This

s is also tied to the p and the t with a line going up from her head,

there making a loop twice as high as her body is long, and then

reversing from there on the right side of the pen down to the p and t

are binding as can be seen from the following distribution.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

t

|

The t also takes its essence from the i, it is lengthened by a fourth and, like the f, has its body cut transversely.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

v

|

We have two kinds of the v and the u, the first is a consonant and is placed at the beginning of a word.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It

takes its origin from the o, I make of the v two elongated commas, the

first I take down from above and without taking the pen from the paper

I bring the other down upwards with the edge of the pen, which I close

with the back of the pen with a slight push.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

From

the consonant v the w is made in the same way, I attach it to the top

of the head of the same first v and make it equal in breadth and

length, just as the other letters of the same shape have equal width,

length and curves to give it more grace.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

u

|

The

other u is a vowel and is made of two ii tied together, get the tail of

the first into the center of the body to grasp the other.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

x

|

I make the x like a pitcher, slanted across.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I

start it with the big side of the pen, and later turning the same on

the flat, draw from the left hand down to the right, then I start the

second line as I also make the head of the c, thus cutting through the

first line in half with a good angle of the pen, turning and twisting

at the end as I make the tail of the little s.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

y

|

The y springs forth from the x, differing only in this that the crotch is cut off in half by her tail.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I

start like the first line of the x, then ink comes up, make her head

like the c, and descend with the cut of the pe to the left hand next to

the first line, and make her tail in several ways similar to the tail

of the f.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

y is also made in another way, binding two tasks together, viz: I come

from below the first task upwards, and sprouting above almost at the

end with the edge of the pen, get it in the flat a little bent across

for the second task, and end it with the tail of the first y.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

z

|

The

z takes its position from the last y, the first task going down I make

at the end of the second, excluding the tail, a little curved line of

the same decency as that which the two tasks of the y garnered together.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This

undertaking of each letter in particular I have wished to describe, for

the common good and good will, and for the greater elucidation of my

teachings, to put together the foundations according to their proper

origin of the Italian letters.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not

making the arrangement according to that of the alphabet, but an

arrangement of all the letters together which take their essence from a

similar origin.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As

also of the identical letters, which are made in different ways and

hung together with several lines from above, as can be seen in the last

tile of the accompanying engraving.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Have

had several experiences of the inexperienced overwriting many letters

two or three times when a line should do so, resulting in you not going

as fast as you should, and obscuring the liveliness, I thought well of

pointing out which letters with one line and which must be made with

two lines.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The ones made with one line are these: a b c e g h i l m n o q r s v u z.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

And the ones made with two lines are these: d f k p t x y.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In

a similar way I have also added here the letters which are started in

the same way, with a small line with the edge of the pen, starting from

the left hand to the right going diagonally upwards as well as those

that end in any way with a small stroke, drawn with the right angle of

the pen.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The ones that start the same are these: i m n p r u x y z.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

And those who end in the same manner are these: a c d e i k l m n t u.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I would like to put these details here, all for the promotion of beauty and the help of those who procession the pen.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

To this must be added the explanations and teachings of the capital letters, which are called Capitals or Majecules.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

but

as this work has already fallen so heavily, and I do not like to burden

myself with copious reason to use the same matter, considering that

they too, for the most part, take their origin from the o and the f,

therefore I have wanted to omit them, leaving it for a better

opportunity,

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In

the meantime I would like to ask the art lovers and beginners to make

do with the Capitals as mentioned, assuring me that from the same

instruction as before it can be sufficiently understood how the Italian

letter can be made large and small starting and ending, as well as by

what rules and degree one must keep, to be able to write perfectly with

the same hand.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Education of the large and small Dutch letters.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Instruction of the Textur Letter.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Coming from the teaching of Dutch letters, I shall now begin with the Textur letter, which is probably the oldest of the Grove and Bastard letters.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It has been in general use among the religious who have written the sacred legends and Masses in such a letter.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

She

is made in various ways: some pressing close together, with a thickness

of one-eighteenth of her length, others a little further apart, and

somewhat thicker, namely, the same part of her length, which also

pleases me worse than the thin narrow one, whereas in it a better

measure can be preserved and it has a better standing.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Perpendicularen line is the one that makes most of her body, because her stance is usually elongated.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Her

head and feet are usually made elongated and squared out, beginning and

ending either below or above, with the edge or flat of the pen.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Some

hang heads and feet together, and some don't, which I also consider

better because they look cleaner and are easier to read.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

lines that run across the body are drawn half the width of the pen,

starting from the right hand to the left, always matching the heads of

the further letters as you can see in the examples.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fracture letter instruction.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Fracture letter has evolved from the High German, where it is also used because it is more beautiful and graceful than the Texture and also because it is easier and faster to write.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

High Germans usually write rather boldly and sharply as they do with

all their writings, which are usually written with a thick pen, and

disdain all thin writings whose body and limbs are equally thick and so

scraped as if they had tuberculosis.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

And,

to tell the truth, there is nothing more graceful and more agreeable

than a well-posed body, that is, a little bold writing and a little

subtlety on the cutting edge.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This Fracture

letter has no difference other than that the heads are drawn with a

stroke, firstly they start with the edge of the pen and end with the

flat , again starting with the flatt and ending with the edge, because

unlike the Texture the heads

are made elongated and flattened, and that the feet of the mm and the

nn below should be square like a rhombus, and some others a little

roundish, in the manner of the semi-stretched round elines, indicated

above in the figures, and still have other feet in the way of curved

diamonds, as you can see in the examples.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Instruction of the Bastard letter.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This Bastard letter has a completely different character than the Fracture letter, although those who have practiced the Fracture letter a lot will also be able to write the Bastard letter, because it is also written almost the same way except that one has to make the body rounder and squarer.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

looking letters should be flat on top and headless, although Scribes

also make them with a head for the sake of giving them some change.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The semi-curved round lines are the ones from which most letters, which are lacy round, are made.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Perpendicular

line for all letters that go straight down and whose feet touch curved

diamonds, except those of the hh ff mm and nn, which have no feet but

must be blunt and flat below.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I make her limbs as long as the body, except for the d and the t, which above the line should only look half her length.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

You may measure and seek the position of its thickness and breadth from the following foundations.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

There are other ways of writing coarse letters, both

High German and Dutch, which are called Cantzellery writings, lying and

oblique, but as I have said only want to deal with the particular and

most common (although without insisting on that I could impart to

enthusiasts all sorts that six books wouldn't be enough to understand

it all). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I shall continue with our general Dutch letters, to describe her stature and qualities according to the gift I have been given. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Department of general Dutch letters.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

French letter instruction.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

English letter instruction.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Instruction of the High German letter.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It

remains to speak a little about the High German hands, which I wanted

to deal with last because they differ most from our letters, although

they are not the worst.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

For

as the Fracture is well regarded, small and great, and then also the

Canzzelery in various ways with its Lines and Capitals, so it must be

confessed that these have no less ornament and grace than those of the

other Nations.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

And the importance of the general High German hands, as well as no less pleasing, as useful and skillful to master quickly.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pleasant

I say because they are plump and well fed, and able to lead the way,

because this letter falls round and short, and is well connected, so

that it must be rolling and speeding along.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The most important are the Round and the Curente hand, of which the Round is the most beautiful.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

They

do not differ much from each other, except that the Round is written

somewhat shorter in body, and that it falls backwards, as opposed to

the curente, and is therefore also written with various kinds of pens,

as I have explained before.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

There are even more types of High German writings.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

But

in order not to overload the memory and understanding of the novices

with too much confusion of various ways, I have only included here the

nature and fundamentals of these two.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

From

which experience one can easily arrive at the manners of all others,

consisting most of the changes in the variety of the n m, for as the

High German masters themselves write: VVie manncherley m / so vil

artenschriftenn (so many mm's, so many artful writings).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As

several aficionados have seen some parts of my books, made them think

that some Capitals which are in the beginning of Matter might be a bit

too much for those who are first beginning to study the art of writing

to pursue after her, I have thought it right to add these Dutch,

Italian and Spanish capital letters to the conclusion and end of this

book.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

So

that the novices and students should have no cause of impediment, to

sail well at the beginning, and to come to their good will and to write

well and perfectly.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

others who are a little more adept at the actions of the pen and who

are eager to progress, and who do not yet feel they are good enough,

will be allowed to practice in the preceding Capitals, as well as in my

exalted poems.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Which,

though not according to the order of the ABC, yet I have put forward,

for those who will write Matter books in such a way, may find therein

the whole ABC, none of it omitted, but made up to the z, yes, nearly

two or three of each letter, which I did to satisfy every one, and lest

I should be accused of not having wrought as much for the one as for

the other.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I

beseech all pen-lovers to thank my work, and to do more my goodwill and

affection which I have had, but which Mr. Poormoney has prevented,

though he has lent my hand in this work liberally, and that my book

costs me great expense, and I myself end with difficulty and in great

poverty, but:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Like a woman, after she has given birth,

The pain forgets, when she sits at rest:

The labor also, which has weighed me down,

To bring forth, this work in its right nature,

Now that it's done, I've forgotten most of it.

FINIS

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2023 - Bach Museum Leipzig

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Back to B

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|